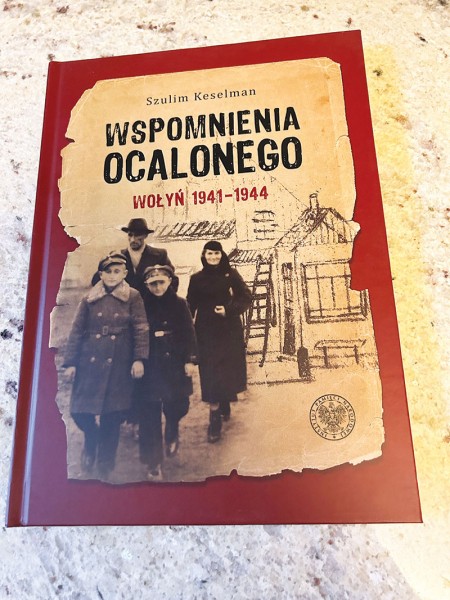

A Holocaust Survivor’s Story Lives On

Joe Keselman was 7 or 8, living in his native Poland in the late 1950s, when his father Szulim shared with him that he had written a memoir of his harrowing escape from the Nazis during World War II. He brought out two school notebooks filled with his writing, and he read those notebooks to young Joe over the course of a few months, a couple of pages at a time.

At 17, Szulim lost his whole family during World War II, in the Nazi “Holocaust by Bullets” perpetrated in Ukraine. He survived by fleeing the Lokacze ghetto in his native town right before its massacre, initially hiding in surrounding forests, and later, with the onset of severe winter, being given shelter and sustenance by a Polish farming family.

The story made a huge impact on the boy. “I really didn't know anything about what happened to him or to his family,” recalled Joe. “And after that story, I was marked for life, because clearly that story and then the Holocaust as a whole has become kind of an obsession.”

Young Szulim fled to the forests near his town of Lokacze, where he lived for several months on what he could forage. With the onset of a harsh winter, he knew that would no longer be possible, and in desperation, he sought shelter at a local farmhouse. His father, who had owned a small shoe shop, had come to know the Stemporowskis and spoke of them as very fine people. Szulim had never met them, but he sought them out. The Stemporowski family took him in, hiding him in a hayloft and bringing him hot food every day for four months in 1942-43. Their cousin Loda Szalinska joined them in the effort, putting themselves in the line of fire; if the Nazis had discovered them, the entire family would have been shot.

After the war, Szulim remained in Poland and married Lidia in 1951. They had a boy they named Jozef, who was to be their only child. Szulim and his family emigrated to the United States in 1963, when Joe was 11. But first, he took them to meet the Stemporowski family on their farm. Joe befriended the Stemporowski children in a relationship that would carry on through the generations.

Joe went on to become a civil engineer and married Kayoko, whom he met in Japan. He took her to Poland several times, even taking her to the Stemporowski farm. For their honeymoon in 1984, they went to Joe’s hometown of Wroclaw, a beautiful city on the Oder River, where she met Joe’s grandmother. On a subsequent visit, Joe took Kayoko to meet the Stemporowskis, and during their visit, they spotted a pair of storks nesting on the chimney of the greenhouse Joe’s father had helped them to fund.

“The Stemporowskis said that was a good sign, so I was very cheerful,” said Kayoko. “And the next year, Julie came to us.”

When their daughter, Julie, was old enough to travel, they took her to meet Joe’s grandmother in Wroclaw. They went on to have another daughter, Alissa, and they raised both girls to appreciate both their Polish and Japanese heritage. But life was busy, and it wasn’t until last summer when the girls, now grown and with careers and husbands of their own, were able to really see their father’s homeland for the first time.

Szulim passed away in 2006. Over the past few years, Joe has been immersed in following up on his father’s World War II memoir. He had the book published in Polish in 2022, and has gone on to translate it into English and seek a publisher in the United States.

In a parallel process, he sought to honor the Stemporowskis with the Righteous Among the Nations honor, the same one that was granted to Oskar Schindler who was credited with saving the lives of 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust; his story is told in the 1993 Stephen Spielberg film, Schindler’s List. And so it was that last summer, on the family trip of a lifetime, the girls met the descendants of the families whose sacrifice had made their own lives possible.

Joe Keselman, center, with his two daughters, Alissa and Julie, to his right, and Joe's Ukrainian cousin Vanya with his wife Anya, on his left.

“They’ve been fortunate in knowing and experiencing much more from the Japanese side of their heritage,” said Joe. “So when this opportunity came around, I thought, ‘I want to combine this and spend a few days in my birthplace and show them around, show them the neighborhood where I grew up, and then after that, we would travel to Warsaw. And in Warsaw would be an opportunity to, first of all, meet the Stemporowski and Szalinska families.

“And I also looked at it as a chance to pass the torch. You know, if Julie and Alissa hit it off and made friends, there might be a chance that this very special friendship and relationship would carry on after our generation.”

Together they celebrated the success of that initiative, a ceremony to honor the Stemporowski and Szalinska families with the titles of Righteous Among the Nations by Israel’s Yad Vashem. These titles are granted to non-Jewish individuals who, at ultimate risk to their lives and without any recompense, saved Jews from Nazi persecution during World War II.

“By the time my dad had finished translating Grandpa's diary, I really felt like I was old enough to digest it, and it was almost like meeting a younger version of him,” recalls Julie, now a massage therapist and marketing professional at 33. “And I have, from a fairly young age, understood that my existence was contingent upon his survival and the kindness of others.”

Those “others” became flesh and blood people during their journey and, by the time the trip was over, friends who would come to share a special bond for life.

They also began to understand the sensitivity and beauty of their father’s culture in a way they had never had a chance to fully comprehend.

Wroclaw's Market Square, with the famous Gothic Town Hall illuminated in the background, from left: Alissa, Vanya, Kayoko, Anya, and Julie.

“I was just so moved by their graciousness,” said Julie. “We were being treated almost like guests of honor when really, in my worldview, we were the ones who had everything to thank them for. Some of the people were crying when they met us. And we were embraced more warmly than I know how to embrace the people who are close to me.”

The ceremony honoring the two families was an eloquent testament to Poland’s deep connection to its history. It was held in the historic Belvedere Palace in the nation’s capital of Warsaw, with the Stemporowskis and the Szalinskas being just two of the many families to be honored that day for having risked their lives in similar circumstances.

“And what was really wild was that the one thing I did not know before the ceremony was that they rescued more people; they were honored not just for saving my grandfather's life, but for saving the lives of two other people.”

They were pleasantly surprised to find that many of their Polish counterparts spoke flawless English. The ceremony that ensued, which was simultaneously translated, was a powerfully moving event.

Mietek, one of the grandsons of Julian and Julia Stemporowski, spoke briefly but profoundly on behalf of the family. Julie paraphrased the comments from her recollections.

Wroclaw's impressive Gothic-style Old Town Hall, which has stood at the heart of the city’s rynek, or town square, since the late 13th century.

“He said, ‘Obviously my grandparents can't be here to speak, but I'll try my best to imagine how they would have received this.’ And he said that they would not have viewed what they had done as anything special, that it was just what you do as a human. The idea of celebrating it with a ceremony or receiving a reward for those acts of service would have been beyond their comprehension, let alone expectation.”

For Julie, the takeaway was tremendous. “I wish everyone could experience such closure for wartime… I mean, very few people get to survive and then get to maintain connection and carry it through multiple generations, and then really honor the best outcome of a horrific circumstance in such a special way.”

She shared a quote from her grandfather’s memoir as a reflection of the sentiment she felt from the descendants of the Stemporowski and Szalinska families:

"We realized that only an exceptional person, with a noble and courageous heart, would agree to shelter a Jew in those times. Especially since I did not possess anything, not even to pay for my food."

The girls are staying in touch with their new friends via email, and in one case, Instagram. And Joe couldn’t be happier.

It’s been nearly 70 years since those two families took the ultimate risk to save Joe’s father and several others. “And then that act keeps on giving, so to speak,” said Joe. “And it's bringing people together from very different walks of life, different cultures, different places. And it just kind of illuminates their relationships.”

In the Footsteps of their Father

During their trip to Poland for the Righteous Among Nations award ceremony, Julie and Alissa joined their parents on a tour of Warsaw and their father’s hometown, the beautiful river city of Wrocław, the capital of Poland’s Silesia region. Situated on the Oder River, the city has more than 100 bridges and an abundance of parks and forests.

Wroclaw, which was known as Breslau when it was under the control of Germany, looks back on more than a thousand years of history; it has been a part of the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Poland, the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, all of which contributed to a multicultural heritage and a cityscape that is a feast for all the senses.

Joe took his family to tour the quiet neighborhood where he grew up, with its market and its school, the grassy park near the Odra River, the fish store, and the air raid shelter where he would play with his friends. Then they went to the heart of the city’s history in the Market Square, with its ornate Old Town Hall, a showcase of bourgeois Gothic architecture, and also the Gothic St. John the Baptist Cathedral.

“The Market Square is very charming, with stone streets and colorful facades of the buildings… Not quite as punchy as what you would see in Mexico, but very, very cheerful, bright colors.”

Other architectural and historic standouts included Ostrow Tumski, or Cathedral Island (where the city was originally sited), and Centennial Hall, an architectural masterpiece and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, renowned for its pioneering use of reinforced concrete and its iconic, soaring dome.

Home to 22 universities, the city has a youthful and vibrant feel, with a lively arts community as well as a historic foundation in the sciences: the University of Wroclaw has produced nine Nobel Prize winners.

What stood out most to Julie about both Wroclaw and Warsaw was the way that both cities rebuilt after being destroyed by bombing in World War II.

“The cities were rebuilt to be perfect replicas essentially of what was there before,” she said. “Both cities have modernized some, but there is so much care taken with restoration and preservation because what was already there was so special. I loved seeing that; it was so uplifting, especially given the destruction that is rampant right around them. It gave me a lot of hope.”

The girls were a little nervous about dining options because Julie is gluten intolerant and Alissa is vegetarian, so they were anticipating challenges and had come up with a backup plan. “But that was not a problem at all. It was so easy to eat, and the food was wonderful.”

One thing she noticed was that certain vegetables had a much more potent taste.

“The potatoes we ate in Poland had such a strong taste compared to here, and they were really great. One of the dishes that was new to me that I loved was a soup that was served at the (Belvedere) Palace, and it looked just like a cream soup. And I was expecting it to be like potato soup. But it tasted like pickles; it was a creamy pickle soup and it was delicious. And I'm going to try to replicate that as soon as possible.”

One of the city’s most endearing features was the collection of brass dwarves placed around the city in a variety of contexts. Originally, they were crafted to represent the city’s laborers and commemorate the Orange Alternative, a Polish anti-communist movement that employed absurdist art as a highly effective tool of resistance. Now more than 600 brass dwarves draw tourists on “dwarf hunts” throughout the city; you can buy a map from the tourist agency for 10 złoty, or about $2 USD.

The dwarves all have shiny spots, said Julie, because they are said to bring good luck and make wishes come true, so everyone rubs their heads and noses. The family had an especially poignant moment when Joe’s Ukrainian cousin Vanya and his wife Anya were able to make it through the war-torn country and cross the border into Poland for a brief respite.

“They traveled 21 hours on a bus to meet us, and they had never left Ukraine before,” said Julie. “And we all rubbed the top of one of the dwarves’ heads and we made a wish to meet again in Ukraine. They said, ‘We wish to have you at our home.’”

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.