The Jaybird/Woodpecker War

An ‘Undertold’ Story – Not a Memoir, Part 7

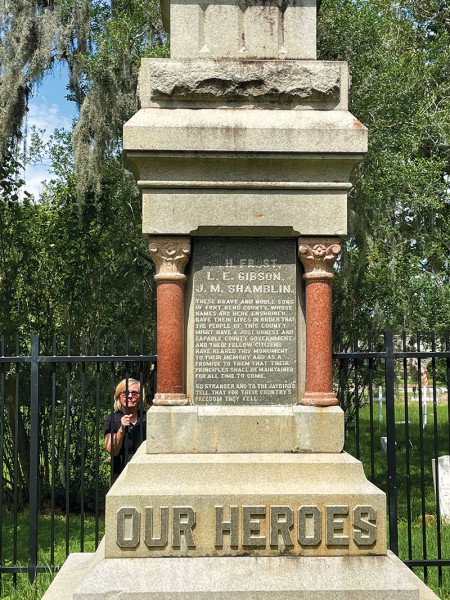

A RELIC This monument is to honor members of the Jaybird Party who died for the “cause” of restoring an all-white government to Fort Bend County. It stood in downtown Richmond from 1896 until 2021 when it was quietly moved to Hodges Bend Cemetery in Sugar Land, Texas, on land originally deeded by pioneer Stephen F. Austin. (Photo: Melissa Noble)

Why am I standing in a very old cemetery getting bitten by ants? After reading a series of articles my father wrote in The Fort Bend Reporter in 1958, I wanted a first-hand look at a monument I remember as a child. The “heroes” in this case were men who died between 1888 and ’89 for the cause of restoring all-white government to Fort Bend County.

I was recently gobsmacked to learn this: Between 1869 and 1889 Fort Bend County enjoyed a bi-racial government. Well, not everyone enjoyed it. But it happened anyway. Until it didn’t.

We moved to Fort Bend County in 1955, where my dad, Clymer Wright, took over the family newspaper, The Fort Bend Reporter and slapped the word Independent across the banner. By 1958, he had decided that something called The Jaybird Democratic Association of Fort Bend County had to go.

We were among the newer families to a community of deeply rooted descendants from among The Old 300, the first Anglo American settlers who arrived with Stephen F. Austin when Texas was still part of Mexico. Together their families started large plantations, went through the Texas War for Independence, the Civil War, and their own side skirmish called the Jaybird/Woodpecker War.

After losing the Civil War, plantation owners faced the reality that their slaves, now called Freedmen, had the same voting rights as whites. By then the population in Fort Bend County was 20 percent white and 80 percent black. The plantation owners not only lost their slaves, they were completely outnumbered at the ballot box.

For two solid decades, Fort Bend County elected officials served side by side, in a roughly 50-50 ratio of Black to Anglo, including the first Black sheriff in the nation, Walter Moses Burton, who would go on to serve in the Texas Legislature.

Leslie Lovett, who currently teaches history at The Kinkaid School, wrote her Rice University Master’s thesis on this subject in 1994. Lovett made this observation: While the county certainly had its share of violence and planter resistance to emancipation and black enfranchisement, what is striking about Fort Bend is the degree to which the planter elite (plantation owners) cooperated with bi-racial county government.

White men, including bankrupt plantation owners, campaigned for the Black vote and won. The former slaves, then called Freedmen, (likely just learning to read) were careful to vote in a roughly 50-50 racial mix. Meanwhile, with the help of the Northern-organized Freedmen’s Bureau, anti-slavery Christians from The American Missionary Association, and others, the Freedmen started their own community, now called Kendleton. White women, some from plantations, served as teachers to their former slaves.

Meanwhile, a group of young white men started itching to get their all-white government back. They formed something called The Jay Bird Democratic Association (they originally spelled it with two words, Jay Birds). They called their opponents the Woodpeckers, those duly elected to office, who needed to come out of their holes. A year-long battle culminated in a final showdown on the streets of downtown Richmond on August 15, 1889. Texas Governor Laurence S. Ross, a former Confederate General, intervened, declared martial law, and facilitated the Jaybird plan to restore all-white government.

Tragically, Black citizens lost the right to vote for some 64 years until 1953 when the Supreme Court finally ruled their white-only provision illegal. But the Jaybird party itself continued to run elections, though technically no longer refusing the Black vote.

In The Jay Birds of Fort Bend County by Pauline Yelderman, published in 1979, Yelderman quoted an editorial published by my father on March 27, 1958 on what turned out to be the last Jaybird primary. This appeared on page 272 in the final chapter; Yelterman wrote:

After briefly reviewing the history of The Jaybird Association, Clymer Wright, the editor wrote.

“We can see no reason for a Jaybird Party to exist today and recommend that the leaders of the Jaybird Party re-evaluate their position in light of the changing times. If the party fails to serve a useful purpose, it should disband. If party leaders are determined to continue the Jaybirds, future candidates should band together and give the party the ‘air’.” (Meaning the brush-off, I assume)

Yelderman added:

This editorial was rank heresy. No editor of a county newspaper had ever been so bold as to ask for the demise of the Jay Bird Association.

The Jaybird Party officially disbanded in 1959. The handwriting was on the wall. Was Dad’s editorial the final nail in the coffin? I’d like to think so.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.