In Dad’s World War I footsteps

An estimated 20 million dead, 21 million wounded, and 7.7 million missing or imprisoned. It began in 1914 as just another European war – and by the time it ended in 1918, it came to be called the War to End All Wars. An unduly optimistic appellation, as it turned out. With the Great Depression and World War II right on its heels, it became the war eclipsed by history. Now, as the centennial of Armistice Day, the end to World War I, approaches on Nov. 11, the Great War is getting a fresh look, by researchers and travelers alike.

Attorney Kelly Frels grew up knowing his father had fought in World War I. When he and his wife Carmela saw a PBS special series last year on the war, they pulled out his father’s “memory box.” There, along with a collection of photographs and a pair of U.S. and German helmets, they found the diary he had kept of his service in the American Expeditionary Forces of the U.S. Army in Northern France in 1918 and 1919. There, too, was his epic battlefield poem about the watershed Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

That battle, as war historian Geoffrey Wawrow wrote for Time magazine on Sept. 26, its 100-year anniversary, became a turning point in the war. The British and French had already lost more than 3 million men between them. Kelly’s father, a schoolteacher by the name of Leon A. Frels, was among the 350,000 U.S. troops that pushed the German forces back out of France – a decisive offensive that ultimately shifted the balance in favor of the Allied Forces.

Inspired to learn more, Kelly and Carmela decided to extend a planned trip to Europe. They were already slated to join a late April riverboat trip to the Netherlands and Belgium to see the tulips in bloom, so they decided that afterwards, joined by daughter Catherine, they would retrace the footsteps of Kelly’s father in Northern France. Their foray into the past opened their eyes to the bitter realities of that war, and the way it set the stage for the next one.

Kelly had the diary transcribed and used it as the basis for their trip. An alum of The University of Texas at Austin, he reached out to the Flying Longhorns, who found a retired French college history professor, Jean-Noel Mesnil, to serve as their guide and driver. Jean-Noel used the diary to plan an itinerary of the towns and locations mentioned.

Kelly and Carmela Frels with daughter Catherine (from left) retraced the steps of Kelly's father in the World War I battlefields of Northern France. At the base of the American Memorial at St. Michel, nature has healed the scarred landscape with lush greenery.

The Frels’ home base amid the rolling hills of Verdun was the Château des Monthairons. This 19th century turreted castle served as a hospital for the Allied forces during World War I and as a German military headquarters during World War II. The Chateau has since been converted to a hotel and spa, where the granddaughter of Gen. John J. Pershing stayed during the commemoration celebrations, as well as the Eisenhowers in their day.

They began their trip where the Second World War ended: in Reims, the unofficial capital of the Champagne wine-growing region, where then-Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had his headquarters during the Second World War, and where the Germans signed their surrender. Not far from there, in a railroad car in the forest of Compiègne, the Armistice for World War I was signed as well. It was a good place to put everything into context, Kelly said, because of the way it pulls the two wars together.

“The maps on the wall had pictures of all the battle sites and transportation systems of World War II,” said Kelly. “Included in that was Verdun… and Le Havre, France, where my father’s ship landed in 1918, when he got shipped over from the U.S.”

Leon Frels was the penultimate child of 13 born to German immigrants in the town of Taiton, not far from El Campo, Texas. He was only 22 at the time of the first draft since the Civil War. His older brother, Louis, was eight years older and had already been serving in the National Guard.

“Dad reported for induction in San Antonio on September 19, 1917, where he and his fellow draftees underwent training before being shipped to South Hampton, England on June 12, 1918, aboard the “Olympic,” then to Le Havre, France, on “King Edward the VIII,” Kelly wrote in a report he shared with family and friends.

Leon Frels was a peaceful, sensitive man, Kelly says. He was not a warrior by nature. He served in the signal corps; a lover of literature, he listed the books he was reading in his diary. That literary affinity went on to inspire his battlefield poem, “The Shocking 360th,” which celebrated the victory from the perspective of the 360th Infantry of the American Expeditionary Force.

While the death toll of World War II was significantly higher, 10 million soldiers alone died in World War I. The total deaths of 20 million at that time was staggering. The intensity of the trench warfare during World War I led to battles with astronomical casualty rates – among the highest in history. The Battle of Verdun alone, for example, ended with nearly a million casualties.

The Frels were taken aback by the sheer bloodiness of it all.

“The ammunition and weapons tell a part of this story as to why the war was so deadly,” said Kelly. “They used 20th century weapons with 19th century tactics, with trench warfare as close as 100 yards apart, shooting at each other with machine guns and rifles while being bombarded with mortars and heavy artillery." Poison gas was another constant threat.

Conditions in the trenches were horrifying, standing for days, even weeks, in the mud and cold under heavy fire, infested with rats and lice and surrounded by death.

"To give you an idea of how deadly it was, the trenches were protected by steel piers. Soldiers strung barbed wire between these piers at the front of the trenches to create a barrier," Carmela said. "As enemy soldiers advanced, they had to cross the barbed wire. If killed while crossing, their bodies would hang there. They could not be rescued or removed because of the fierceness of the battles, so the bodies remained on the wires and deteriorated until only their clothes remained – so soldiers referred to that as 'the clothesline.'"

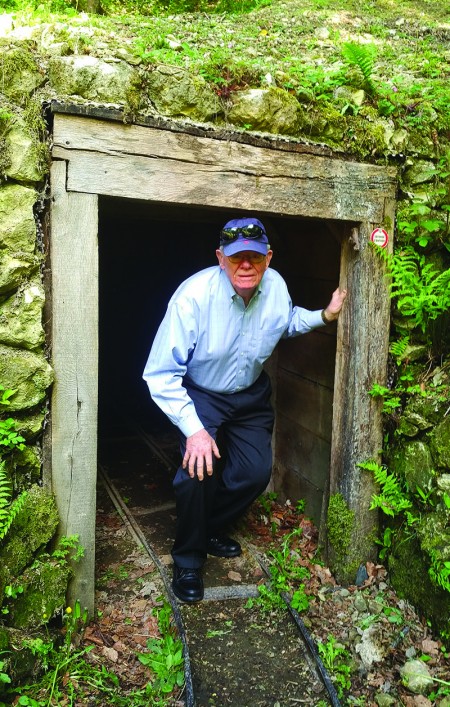

Kelly Frels emerges from a tunnel into a mountain in Northern France, where World War I French, British and German soldiers placed explosives to blow up each other’s positions on the mountain itself.

Several of Leon’s diary entries were of historical significance. He describes “going over the top” and “suffering significant casualties” in the battles of Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

“‘Going over the top,’ used by Dad to describe soldiers exposing themselves to rifle and machine gun fire by getting out of the trenches and charging the enemy, is a phrase that continues in today’s description of being involved in events of exposure,” wrote Kelly.

The Frels visited the site of the first offensive action by U.S. soldiers in WWI, the battle over the Saint-Mihiel salient, an effort east of Verdun, France, that pushed the German soldiers back toward Germany. Then they made their pilgrimage to the site of the second major effort of the U.S. troops, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Leon’s entry from Nov. 11, 1918: “The war is over boys, let’s build fires and warm our feet. Bosche finish. Bosche finish (“Bosche” was WWI slang for German).” He continued to state he was relieved to not hear any more “mine wavers and wiz bangs,” a reference to the German minenwerfers or mortars whose shells continually exploded above the trenches and spewed deadly shrapnel.

The Frels’ full immersion in the story of the war plunged them into some of humanity’s darkest hours, making their way into the trenches and battlefields, visiting the memorials and museums. Some towns had been obliterated – nine villages in the Meuse department alone – and, as a memorial to their loss, the French had decided not to rebuild there.

But always they would emerge into the sunshine and the green rolling hills of Northern France. Families would be picnicking and children playing at the memorials built to honor the sacrifice of those who gave their lives.

The Frels had traveled here before with a much lighter focus; as part of traditional champagne country, the rolling hills around Reims have long attracted travelers. This year, with the centennial of WWI, the area took on additional significance.

“The scars of war inflicted on the landscape where millions perished in 1914-1918 have been replaced with fields and forests, with the exception of noticeable depressions in the earth caused by artillery bombardment especially around the Verdun area, where that intense battle was fought,” wrote Kelly. “It is amazing how nature can heal the landscape.”

Leon Frels, like most combat veterans, didn’t talk much about the horrors of the war. “His comments, when made, were more about the suffering of the civilians and the soldiers affected by the conflict. He felt that war was a terrible waste of people and a squandering of resources. He believed that world leaders should take extraordinary caution to avoid wars, because what started as another European war of seemingly limited scope became the first world war.”

World War I travel tips from the Frels

The Frels’ epic journey was an unusual one, involving three generations: Kelly and Carmela Frels, their daughter, and Kelly’s late father, Leon, guiding them through champagne region of France by way of the pages of his war diary. Here we share their recommendations with a few of our own.

The rolling hills of that region have always been a rural farming area, now of bright yellow rapeseed, used to make canola oil. The landscape around major battle sites is still punctuated with holes left by World War I artillery shells. Champagne houses Veuve Clicquot and Pommery may be visited near Reims.

The Memorial de Verdun, a first-rate museum as well as a monument honoring the many who died here, is excellent. Nearby, two American cemeteries honor American warriors, their graves marked by white crosses. In contrast, at the German cemetery, the graves are marked with black ones.

In the vicinity, one can visit the site where U.S. Marines fought the vicious Battle of Belleau Wood, a forgotten assault that launched a bloody new era for the Marine Corps; their pet bulldog mascot became a Marine symbol.

Built in 1857-59 on land held by the original family from a 1685 dowry, the Château des Monthairons was purchased by the Thouvenin family in 1935. It is outside the town of Verdun in the area of U.S. Army battlefields of the St. Mihiel Salient, where America’s first D-Day was fought, and the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the largest and bloodiest battle in American military history. Modern-day visitors will have the chance to contemplate that history while savoring the peace of the French countryside, and the Château is the perfect place to do so. The Frels stayed here because it is in the middle of the towns of Grandfather Frels’ diary.

They were put in contact with their guide, Jean-Noel Mesnil, through Becky Robinson of Departure Lounge in Austin ([email protected], 512-922-1393). Departure Lounge has a working relationship with The Flying Longhorns of The University of Texas at Austin’s Ex-Students Association, and Robinson arranged for their guide and accommodations at the Chateau through their French Travel Agency affiliate, Decouvertes.

Reims is in the middle of the champagne country of France. In fact, when people visit France to see the vineyards and champagne houses of renown, Reims is the center of that activity. In that regard, the area around Reims is the center of champagne in France. Since the Frels had already visited those champagne houses, the caves where the champagne is stored and the tasting rooms in a 2008 visit, they chose a different course on their 2018 trip. Reims is a modern city today with a university and an outstanding hospital. With Dwight D. Eisenhower’s World War II headquarters being there, where the Germans surrendered in 1945 to end that war in Europe, Reims is a historical location from the Second World War, but can help orient World War I researchers as well.

In addition to the Museum of the Surrender associated with Eisenhower’s headquarters, the Verdun Memorial Museum is outstanding, with captions and stories are in French and English. The American Cemetery at St. Michel has some materials, but falls short of being a museum.

Looking for the lighter side?

Having visited the champagne district before, the Frels decided staying at the Château and enjoying French champagne was appropriate. The Château is located outside a small village near Verdun. You have to know where you are going to find it. It is reminiscent of a castle, yet it is very different – much more inviting. The food was served in an elegant dining room, and the wines matched the food in quality. One would have to travel to Verdun from Reims to get there or to the battlefields where the Americans fought.

The Thouvenin men are both gourmet chefs, and their wives operate the hotel and spa. Gourmet dinners paired with fine wines, served nightly and prepared by the family, attracted hotel guests and travelers as well. One evening, Catherine, their host, served pigeon from the cote outside their room’s window.

In the village of Stenay, where the American Forces were in the Meuse-Argonne offensive on Nov. 11, 1918, a farmer they stopped in the town said there were no remnants of either war remaining. There were just pastures and fields and people living out their lives in the small villages. Many villages were never rebuilt beyond a few buildings, while others were redeveloped.

The Frels mostly ate at the Chateau, and the luncheon restaurants (cafés) they enjoyed when driving around were all over the place. “One thing about France – we never had a bad meal!” wrote Kelly.

One of the reasons the Frels had to arrange a self-guided trip was that the big trips planned for alumni groups and tour companies relating to World War I have concentrated on the Western battle areas, and few of them have focused on the Verdun area in eastern France where the Americans were involved – “probably a hangover from everyone always concentrating on World War II, where the main battles were in Normandy and Belgium, far to the west of Verdun,” wrote Kelly. “One can go online and find self-guided tours of the areas where Americans fought, but we wanted ours personalized to fit the diary entries.”

The Internet now has more information about World War I and tours covering the areas where the American forces saw action than when the Frels started looking a year ago.

“I suppose the publicity about the 100th anniversary is stirring the creative juices of would-be guides,” said Kelly.

A number of websites now offer self-guided tours, but Kelly strongly advises hiring a local guide who knows the area.

“Even our knowledgeable guide got confused with where to go from time to time. I would definitely not do a self-guided tour. If nothing else, the language difference is a challenge. All the signs are in French, and GPS doesn’t always work,” wrote Kelly. “Also, remember that this area has not been an American tour destination until the country woke up to the fact that American involvement was important to the Allied victory. This part of France is not Paris or Normandy!”

The Frels had already planned a riverboat tour of the tulip gardens of the Netherlands and Belgium in late April, at the height of their beauty, and they were not disappointed. Their agent Becky at Departure Lounge recommended AmaWaterways, which offered three major tulip viewings, while the others just offered one or two. They were not disappointed.

On the tulip trip, they bought chocolate in Belgium and gouda cheese in Gouda, which Carmela brought home to serve to her needlepoint and bridge groups. Another souvenir: silk ties for family lawyers from The Peace Palace (world court) in The Hague.

For those who are interested in planning their own trip, here are some resources:

greatwar.co.uk: a website created and maintained by three British descendants of 20 veterans of that war, based on their own research. The site is chock-full of resources regarding different tours, destinations and even advice for tracing your own World War I family history. Their self-drive itineraries – if you dare – are drawn up by an expert of WWI battlefield sites. They can also be good background even if do you have a guide. http://www.greatwar.co.uk/organizations/battlefield-tour-companies-self-drive.htm

Auto Europe Guide: for those who are just looking to skim the history and shoot some selfies. Includes a culinary guide to the Western Front, as well. https://www.autoeurope.com/road-trip-planner/france/self-drive-history-tour-of-france/

The Shocking 360th

by Leon Frels

’Twas a cold and dreary evening

In the north of muddy France

When we filed into the trenches

To make the old Hun dance

No concrete walks to greet us

No lights to show the way

But lots of mud beneath us

And no chance to hit the hay

At last we reached our dug outs

And we crawled in through the door

We were met by rats and cooties

Who said, "Welcome three six nought"

And the cooties all got busy

Ere the long, cold night was done

Soon we learned to hate the cooties

While we learned to hate the Hun

T'was a cold and dreary morning

When the Reichstag took its place

While they waited for the Kaiser

There was gloom on every face

And the Kaiser made his entrance

In his proud and haughty way

Gazed sternly at the Reichstag

When the chancellor rose to say

Oh great and mighty Kaiser

I have bitter news to tell

The three six o'h is in the trenches

Then a sudden silence fell

Then rose a great commotion

In that room with statesmen filled

The Reichstag pulled their whiskers

"Mine Gott" These men are hell

Behold the Kaiser shouted

As he waved his stunted mit

I have 1600 shock troops

Who will make these Yankees quit

So he issued out his orders

To his dirty drunken gang

Take no prisoners he ordered

And his voice with passion rang

We were standing to at day light

When the Bosche barrage began

Sure enough they are coming over

Give them hell boys if you can

Then our own barrage made answer

And the shock troops have in sight

And the old machine gun rattled

While we pitched into the fight

As the smoke of battle lifted

Bosche were dying by the score

Mercy, Kamerad, Gott Mitt Himmel

We give up to three six nought

So we shocked the German shock troops

They were shocked beyond repair

When the Reichstag heard the outcome

They stood up and tore their hair

So let this be a little lesson

To the Kaiser and his crew

When he tried to lick Old Glory

He bit more than he could chew

For we fight for peace and freedom

Not to play a tyrant's part

We have millions more to back us

And we finish what we start

Leon A. Frels

90th Division

360th Infantry

America Expeditionary Force

American Exploration Platoon

Meuse - Argonne Offensive

France 1918

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.