Houston’s Holocaust Survivors

And the museum that shares their stories

Ruth Steinfeld, Bill Orlin and Anna Steinberger, here (from left) at Holocaust Museum Houston, continue to share their stories from the Holocaust. (Photo: hartphoto.com)

I gave my first tour as a docent at the Holocaust Museum Houston in 1997. Since then, I’ve given probably nearly 400 tours to thousands of people over the years. Many have asked why I do it, and others have questioned how I am able to lead tours on such a sad topic.

How could I not?

Although my family members include Holocaust victims and survivors, this subject was foreign to me through my high school years. It was not an acceptable topic of conversation, and it was not included in my class curriculum growing up. I was only aware that my surviving relatives disliked Germany back then, and I was taught at an early age never to buy them gifts that were marked as being made in Germany.

Writer Russell Weil's great aunts, Balbine and Hulda Schwarz, at their Houston apartment in 1960, with a mosaic tablet of the Ten Commandments that Balbine made to thank the WWII dead of her adopted country, America. The tablet was placed in the St. Avold Memorial Cemetery in France. (Photo: Weil family private collection)

Two great-aunts from Posen (German-controlled) who were survivors, Balbine Schwarz and Hulda Schwarz, were generous to me and my older brother. When my dad was helping me buy my first car, my aunts wanted to contribute. Their only stipulation was that if we purchased a German-made automobile, they would not ride in it. My first car was American.

The United States Congress, by unanimous vote, established the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980. This moment was pivotal in permitting the Holocaust to become an acceptable topic of conversation. The same year, in another unanimous decision, Congress voted to create the United States Memorial Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

For the 1985 groundbreaking ceremonies, Balbine and Hulda were invited to participate. Not long after, they began to carefully share their stories in detail, and their openness would forever leave an impact on my life. Listening to my aunts’ recollections, I was mesmerized as if someone were reading from an epic novel or movie script.

The years passed, and their health declined. Holocaust Museum Houston opened its doors in 1996. When I saw an advertisement for docent training, I knew I had to be involved. I wanted to keep my family’s story alive and honor Balbine and Hulda.

There were 11 million victims of the Holocaust murdered at the hands of the Nazis and Nazi collaborators. Six million of those victims were Jewish. Those who survived and lived through the horror, including Balbine and Hulda, are Holocaust survivors. In 1996, there were hundreds of Holocaust survivors living in the Houston area. Today, while the numbers have become smaller, those still with us remain committed to sharing their personal stories so that others can learn from the past.

Volunteering at the Holocaust Museum Houston has lead to the opportunity to become friends with many Houston Holocaust survivors. I first met several of them when they came to speak with our class, showing their appreciation for our service and sharing their personal experiences. For them, the Holocaust was a part of their past, but they wanted us to understand how it could affect the present. They needed us to understand exactly what happened between the years of 1933 and 1945.

Their stories are woven throughout the museum’s exhibits, beginning with their lives before to their fates and journeys after this horrific time in history. They have played a vital role in keeping the Holocaust personal and offering the human side to a dark time, so that this history is never forgotten.

As visitors enter the main exhibit, Bearing Witness: A Community Remembers, they are introduced to photos of local survivors’ families living in Europe prior to World War II. One of these has become my favorite over the years, and I always include the photo of a little Jewish girl in Germany smiling on her first day of school in my tours. This young child, Paula Hirschberg Dreyfuss from Oldenburg, Germany, could have been someone I might have known in grade school, eager to learn and meet new friends.

Three local Holocaust survivors, Anna Steinberger, Ruth Steinfeld and Bill Orlin, continue to be actively involved in educating others about lessons learned from the Holocaust.

Anna Steinberger, in front of a photo of Paula Hirschberg Dreyfuss on the girl’s first day of school in Oldenburg, Germany. (Photo: hartphoto.com)

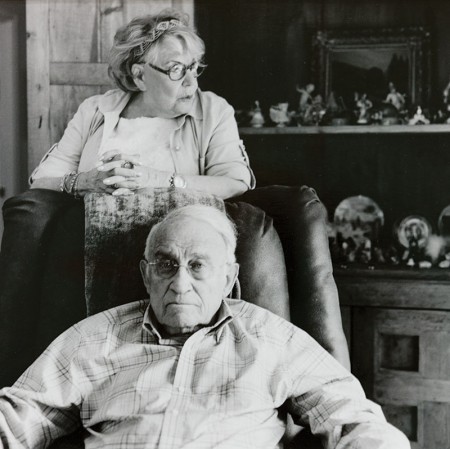

Dr. Anna Steinberger and her late husband, Dr. Emil Steinberger, endowed the docent training program at Holocaust Museum Houston. Anna is always there with a big hug and intelligent observations.

Her family fled Poland to avoid the Nazi regime in 1939, living for six years in Russia before the war ended. In 1940, while living in Alma Ata in the Kazakh Republic, she met a young man by the name of Emil Steinberger, whose family had endured deplorable living conditions. Emil was suffering from malnutrition and was hospitalized. Once he was well enough, Emil and Anna spent time together while their parents became friends.

When the war was over, both families returned to Poland. They found indescribable devastation. Anna’s family lost everything except each other. After spending time in a camp for displaced persons in Kessel, Germany, Anna and Emil came to New York in June of 1948.

Anna Steinberger walking in Poland in 1938 with her father, mother and her uncle, who was a country doctor. (Photo provided by Anna Steinberger)

Starting over in America, Anna taught and conducted research in reproductive biology and served as assistant dean for faculty affairs at UT Medical School-Houston. Anna continues to speak to students and adults from all over the country who come to the museum to learn about tolerance and remembering the past. I am lucky to call Anna a friend.

There is one main message Anna hopes visitors take with them after they have toured Holocaust Museum Houston. “People must learn to live with mutual respect and understanding, regardless of our backgrounds or differences in our economic situation, the color of our skin or our philosophy,” she says. “We don’t always have to agree on everything, but we must do it in a civil fashion.”

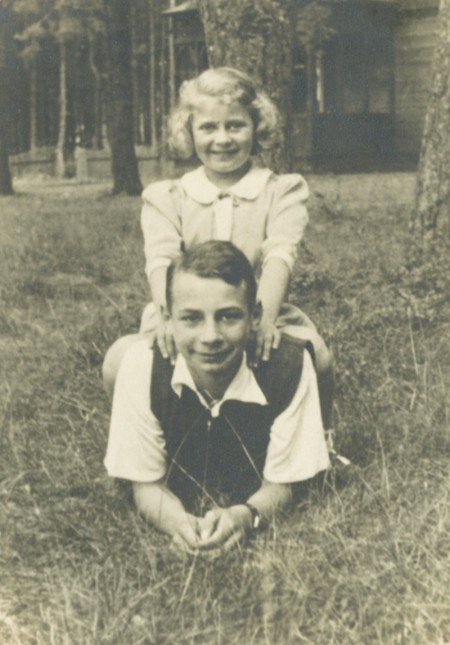

Anna Steinberger was 10 in this photo with her older brother, Jacob, in Poland in 1938. (Photo provided by Anna Steinberger)

Anna strongly believes that only education can change attitudes. As the number of survivors and witnesses to the Holocaust are fewer in numbers, Anna believes that it will be up to docents and educators in the museum to carry on that legacy.

One photo in the deportation area of the main exhibit speaks directly to Anna. “There is a photo of Jewish people getting on a train, and one little girl is looking back as if to question what is happening or what is her future. Where are they taking us?” Anna says she was 11 when the war started and was wondering the same things when the Russians were evacuating her community by cattle trains. Anna always points out this little girl on her tours. “Why is this happening to us?” she says. “Why can’t I just be home and play with my friends?”

Anna remembers a tour from several years ago. Two adult men began speaking to each other in German. Anna understood enough to realize they were making negative comments about Jewish people. After the tour, she asked these men what brought them to the museum. Answering in English, they explained they were visitors to Houston involved in oil exploration, and they came to see what lies the Jews were spreading about the Holocaust. Shocked, Anna calmly replied that they just revealed their tremendous ignorance, and she gave them her advice. “Why don’t you just go to your own museums and see all the records that the Germans kept during the Holocaust? Your own libraries and your own records were recorded by German historians and Nazis who took great pride in eliminating the Jewish population.”

After they realized she had understood what they were saying in German, they both apologized and even waited as Anna walked to her car, making sure she got in safely. “Education is certainly our greatest tool in teaching lessons from the Holocaust,” says Anna.

On the wall of local survivors behind Ruth are the names of friends and family members, most no longer living. (Photo: hartphoto.com)

Born in Manheim, Germany, sisters Ruth Krell Steinfeld and Lea Krell Weems were among the first survivors to talk publicly about their experiences. Ruth continues to bring gentle strength sharing her story and offering wise words, traveling the world spreading hope as a speaker. She was a seasoned docent when we first met, as was her beloved husband, Larry, who passed away in 2015.

Larry caringly took me under his wing when I was training to become a docent. As I showed up to follow one of his tours, Larry took me by the arm to have me stand beside him, rather than among the tour, so I could see the audience react. I learned so much by his small but meaningful gesture that I carry on the tradition by doing the same for docent trainees.

Ruth Steinfeld, with her late husband, Larry Steinfeld, who was born in Hameln, Germany in 1930. He arrived in New York with his family in 1938 to escape Nazi Germany. Larry was a longtime docent at Holocaust Museum Houston. (Photo provided by Holocaust Museum Houston)

After the Krell family was deported to the internment camp of Gurs in the French Pyrenees, Ruth’s mother, Anna, made the selfless decision to entrust Ruth, age 7, and her sister Lea, age 8, to a Jewish philanthropic organization called the Oeuvres de Secours aux Enfants (OSE). As they left the camp, Ruth and Lea never saw their parents again, as both perished in the Holocaust.

The two sisters lived first in a group home and later with a foster family in a small farming community in France. Posing as Catholics, Lea and Ruth were safe only until the villagers began to suspect their true identities. Both were moved to another orphanage, where they remained until war’s end. At 13 and 14 years old, Ruth and Lea came to the United States in 1946 after her remaining grandfather Jakob Kapustin, who was living in the United States, saw their names among a list of war orphans and brought them over.

Ruth (left) and her sister Lea Krell Weems, with their mother, Anna, in Ladenburg, Germany, in 1936. Their mom gave them up to save them and later was killed in the Holocaust. (Photo provided by Ruth Steinfeld)

Ruth Steinfeld became involved with Holocaust Museum Houston during its planning stages, with just five people sitting around a table. For each of these survivors who were not used to speaking publicly about the Holocaust, their belief was that a museum would be a great place to learn. Ruth had much to tell, yet she was not used to sharing her story, even going as far as not discussing the Holocaust with her children, avoiding questions about what had happened to their grandparents. However, during the first meetings when so many showed up in support of the museum, many of whom who were not Jewish, Ruth realized that others cared and wanted to learn.

Through the years, this space has come to represent much more than a museum to Ruth. She has a special connection to the Memorial Room. This peaceful place is adorned with a wall of plaques to honor local Holocaust survivors who have died since the museum opened. “With all the names of the people who were survivors that passed away, it’s like a cemetery we never had,” Ruth says. The remaining walls in this room are highlighted by art installations with messages of remembrance, tears and hope.

Houston Holocaust Survivor, Ruth Steinfeld, stands in front of a slide of her parents in the Destroyed Communities exhibit at Holocaust Museum Houston. Born in Manheim, Germany in 1933, her family was initially deported to the internment camp of Gurs in the French Pyrenees. (Photo: hartphoto.com)

The main message that Ruth has learned herself through the years is forgiveness. During this journey, she faced her past by returning to Germany after a 1981 visit to Israel, making her way back to her childhood home. After holding everything inside, she says, she had a powerful experience of forgiving. “Ever since that happened, I have felt like a new person. I don’t have any anger.” When she knocked on the door of her childhood home, an older German-speaking woman answered the door and invited Ruth inside. As she walked in, the two women began to cry, and they instinctively hugged each other.

When Ruth came to America, she says, everyone kept quiet. “If you had a problem, you were told not to talk about it. Silence is not the way to go. We have to talk. Docents are here to show the museum and to tell the stories. It’s important.” Ruth assumes that same responsibility as she continues to share her story at schools and organizations.

Bill Orlin was 7 when Nazi troops invaded. His entire village was forced into a 50-mile march, suffering abuse along the way. (Photo: hartphoto.com)

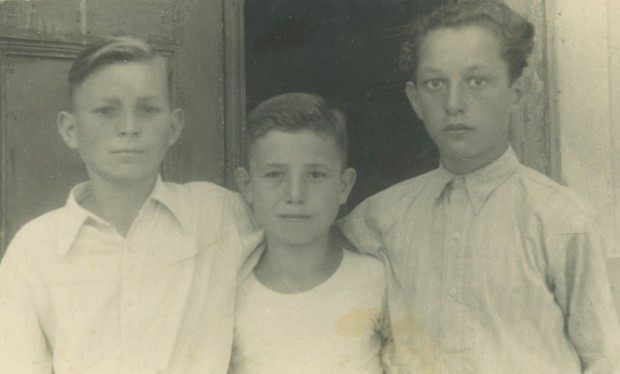

Bill Orlin, originally from the east Poland village of Brok near Warsaw, was forced from his home with his entire family as the Germans took control of Poland. They were forcibly marched to Ostrow Mazowiecka approximately 50 miles northwest of Poland, suffering abusive humiliation. “We walked all day,” says Bill. Their journey took them through Bialystock, the Soviet republic of Belarus, and Uzbekistan.

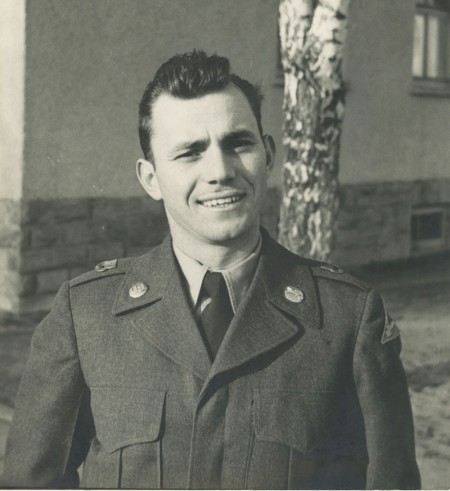

After the war, Bill and his family lived in a camp for displaced persons in Germany. In 1948, they left Germany for Canada, settling in the United States in 1951. Although a newcomer, he felt passionate about his new homeland, and was willing to join the military and defend his adopted country in the Korean War, becoming a part of U.S. forces occupying Germany in the 1950s. While stationed in Germany, Bill became a United States citizen.

After the Holocaust ended, Bill Orlin and his family were sent to a displaced persons camp in Germany. Here, Bill is with his brother Boris and their friend Lou Kerschberg inside the camp in 1948 shortly before Bill and his family left for Canada. (Photo: Bill Orlin)

Holocaust Museum Houston reminds him of the past while teaching new generations of students about the Holocaust. “The docents are the best thing that ever happened to the museum,” says Bill. He went on to describe a tour that he followed where the docent asked the group, “Who is a Jew?” This sparked an important conversation because, as the group members realized, you cannot always identify a Jewish person simply by an individual’s attributes. “No one ever accused me of being Jewish. Italian, yes! Some of the things you have read about Jews having big noses and large ears – that’s all German propaganda.” The docent had touched on an important lesson.

At the age of 86, Bill says he is the only living male Houston Holocaust survivor currently speaking at schools and universities across Texas. His primary message is that this really did happen. “The Eisenhower films in our museum are proof of that,” says Bill. In the Liberation section of the museum’s main gallery, videos of Allied liberators led by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower show the carnage that was discovered as liberators entered each concentration camp. These films were ordered to be made by Eisenhower to ensure everyone was made aware that the Holocaust did happen.

This 1954 photo of Bill Orlin was taken in Germany while he was serving in the U.S. military during the Korean War. (Photo: Bill Orlin)

Holocaust Museum Houston currently is housed in a temporary location at 9220 Kirby Drive while the main campus at 5401 Caroline Street in the Museum District is being rebuilt, with a scheduled opening in June 2019. This new, three-story, 57,000-square-foot home will offer an expansive format to tell the stories of the Holocaust, local survivors, human rights, and tolerance

Survivors, including the treasured Anna, Ruth and Bill, my family members, as well as all victims of the Holocaust, are heroes. As their numbers become smaller, it is vital that their voices continue to be heard.

Balbine and Hulda may be gone, but they both stand beside me with each tour I present. I point out their names on the Wall of Survivors in the museum’s permanent exhibit as a personal acknowledgment to two strong women whose influence on my life remains. Holocaust Museum Houston is here to tell their stories.

Learn more about Anna Steinberger here.

Watch a video on Bill Orlin, with an introduction by Anna Steinberger.

Read more about Ruth Steinfeld and her sister Lea Weems.

Click here to listen to an audio interview of Balbine and Hulda Schwarz.

Holocaust Museum Houston is scheduled to reopen in June, after more than doubling in size. The building’s new name will be Holocaust Museum Houston, Lester and Sue Smith Campus. The Smiths donated $15 million, the largest gift in the history of the museum. Admission to Holocaust Museum Houston is $12 for adults; $8 for active-duty military and AARP members; free for children, students and college-level students with valid ID. Advance reservations are not required, except for group tours of 10 of more. Russell Weil's next tour at the museum is Saturday, Jan. 12, 12:30 p.m.

Editor's note: Anna Steinberger passed away on Dec. 28, 2023, at age 96. Read her obituary here.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.