Kvelling Over Yiddish

Keeping an ancient language alive

Deep in the Berkshires in upstate New York, klezmer music plays through the night, campers compete in a game of Yiddish Family Feud and cozy up around a fire roasting marshmallows and singing Yiddish tunes. Dan Weinstein is in his element.

For the last seven summers, Weinstein, 45, who lives in the Meyerland area, has immersed himself in the language his Eastern European ancestors once spoke. He packs his bags for several days of history lessons, poetry readings, a talent show, and simply chatting with other secular Ashkenazi Jews—non-religious Jews of Central or Eastern European descent—over meals from a kosher kitchen.

The one rule? Campers have to speak Yiddish the entire time.

“Yiddish had always been in the back of my mind,” said Weinstein, a former high school Spanish teacher who now works in compliance at ExxonMobil. He gestures with his hands, and his face lights up. “It was something that got lost, a part of our culture, and I wanted it back. There aren’t many places where a secular Jew like myself can go and speak Yiddish about anything and everything.”

Yiddish emerged in the 10th century and was once the everyday language of Jews in Eastern and Central Europe. That changed during the Holocaust when millions were killed. Today, researchers estimate between 600,000 to 3 million people across the globe speak the language. In ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, it’s spoken as a first language.

Weinstein remembers being curious as a boy when he heard his grandparents speaking in Yiddish. It was their first language, even though they were born in the U.S. Weinstein’s great grandparents were from Belarus, Poland and Lithuania.

The lakeside camp is run by New York-based Yugntruf – Youth for Yiddish. It has no TV and spotty Wifi. The goal: to disconnect with technology and connect with Yiddish. Yugntruf books space at the Berkshire Hills Eisenberg Camp, a Jewish sleepaway camp for kids. Nearly 200 campers from all over, age 5 to 85, attend during the week.

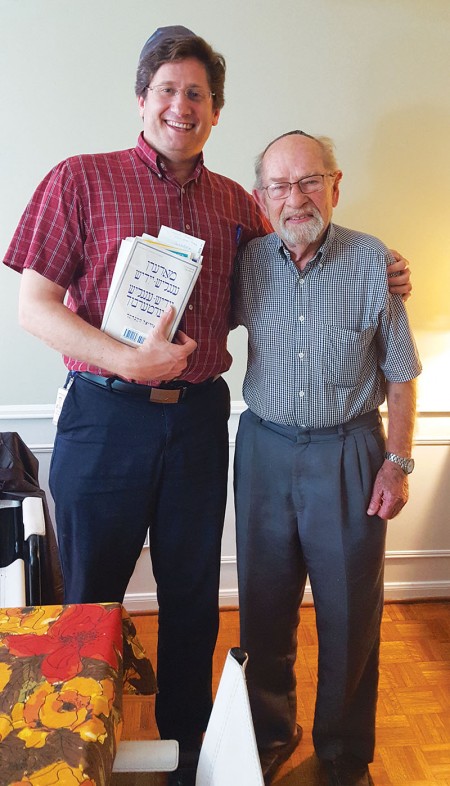

When Weinstein first decided to learn Yiddish, he took beginner classes at a local Jewish organization where he met native speaker Rabbi Pinchas Aloof. Aloof, born in Israel, served as a rabbi in Galveston in the 1990s. Now, in addition to camp, Weinstein regularly meets other Yiddish enthusiasts at the rabbi’s home in Fondren Southwest. To keep up their skills, “we schmooze in Yiddish,” Weinstein said.

On a recent Wednesday, Weinstein and a handful of locals in their 70s and 80s gather around the table in the rabbi’s dining room noshing on a strawberry pound cake and orange halves and cherries piled high on a plate. The men wear yarmulkes. The rabbi leads them in an animated discussion about British Prince William’s first trip to Israel.

“We’re all from different backgrounds,” said the rabbi, who also teaches Yiddish classes out of his home once a week. “The common denominator is mamaloshen, the Yiddish language. It brings us all together.”

One regular is Sara Rozin. Her family, who was from Lithuania, escaped the Holocaust. Nostalgia for her childhood and the country she left behind draws her. “For me, it’s like listening to music. Yiddish has great proverbs. It’s rich in literature. It’s not a dead language.” Chaim Segall, from South Africa, grasps A Yiddish Word Book for English Speaking People. “Every one of us here has grown up with an emotional feeling for the language,” he said. “We don’t want to lose it.” Also a part of the group are Riva Krasnitsky from Russia, who escaped the Holocaust as a child, and the rabbi’s wife, Claire. Claire’s father, from Poland, wrote poetry in Yiddish.

Yiddish now creeps into Weinstein’s everyday life, when texting his parents, or dropping meshuga or oy vey into a conversation with friends.

“A lot of people ask me, why would you want to learn Yiddish?” Weinstein said. “I just always felt like there was something missing in my life. I wanted to learn my ethnic language.”

One year at camp, he spent time with regular attendee Zackary Sholem Berger, a doctor and professor from Johns Hopkins University who translated Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat into Yiddish. Weinstein bought the book for his children, David, 10, and Gabriel, 9, passing down the language to the next generation, keeping it alive.

Yiddish for beginners

Chutzpah (hutzpah), courage or audacity

Kibitz (kibits), to offer unwanted advice

Kvetch (kvech), to complain or gripe

Mensch (mench), a person with integrity

Meshuga (meshoegah), crazy

Oy vey (oy vay), oh no!

Nosh (nosh), to snack on

Nudnik (noodnick), a pain in the neck

Schlep (shlep), to drag or haul

Schmooze (shmooze), to make small talk

Bashert (be-shert), soulmate or meant to be

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.