On the Civil Rights Trail

For retired physician Richard Jackson, travel can serve a purpose far greater than entertainment, and over the years he has endeavored to use it as such. He has long been interested in civil rights, and in 2018 when he read about the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., it piqued his interest.

“A friend, David Wolf, and I decided to go, not knowing what we were going to discover – we really had no idea,” he said. At that time, the Equal Justice Initiative had a small museum about civil rights and they had a bus that offered transport to what has come to be informally known as the Lynching Memorial. “They would drive you up to this memorial (in) an area of the town that was dilapidated and decaying, and someone had gotten together the money to clean off this small hill just outside of Montgomery and put up this amazing memorial.”

As Dr. Jackson walked down the path leading into the memorial, the ground seemed to decline and the rectangular monuments towered up towards the high ceiling.

An image of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Al. (Photo: Equal Justice Initiative)

The creator of the memorial and museum was civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, whose work defending the wrongly convicted is featured in his best-selling memoir and the film Just Mercy.

Inspired by his visits to the Apartheid Museum in South Africa and the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, Stevenson came back determined to create a space for a more open conversation about the transatlantic slave trade and its legacy, and to lift up the Black experience in the United States in a way that hadn’t been done before.

As he told reporter Michel Martin of National Public Radio: “I really wanted to create a space that felt sacred and sober and necessary if we're going to begin to understand our history.”

The sprawling National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which Stevenson called “a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection,” sits on six acres of land and uses sculpture, art, and design to represent the context of racial terror. At the heart of the land is a square memorial structure with more than 800 six-foot-tall suspended rectangular monuments, each of them representing a county in the United States where at least one racial lynching took place. In many cases, there were several.

Blocks from one of the most prominent slave auction spaces in America, the Legacy Museum is steps away from the rail station where tens of thousands of Black people were trafficked during the 19th century. (Photo: Equal Justice Initiative)

There were more than 4,400 racially motivated killings between 1877 and 1950, according to a six-year report by the Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.

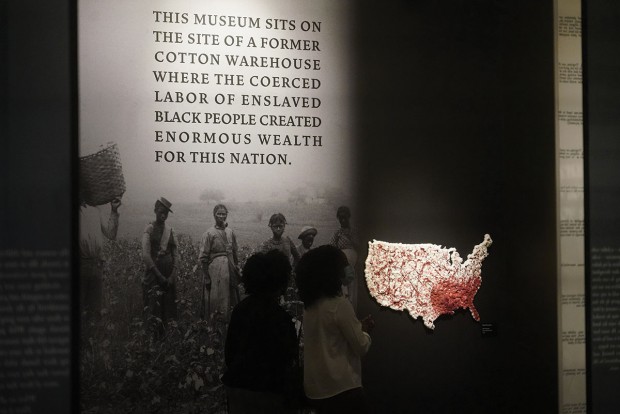

The memorial is paired with the new Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, which is located in a warehouse where Black people were forced into bondage, a few blocks from what was one of America’s most prominent slave auctions. The Legacy Museum, which opened late last year, is a powerful upgrade from the much smaller one Dr. Jackson saw in his 2018 visit, and so he decided to return this February with his wife, Sandy, and three friends from Bellaire – Lainie Gordon, Jacqui Hecht, and Wayne Dorris. “I wanted to give them a taste of this amazing process and I wanted to see it again. It’s so inspiring to me,” he said.

Once again, he was captivated by what he saw.

“It’s one of the best museums that I’ve ever seen,” he said. “It’s an amazing piece of work, and we were very much touched by it.”

The museum is about six times larger than the original one, and state-of-the art; Stevenson raised $20 million to endow the museum and build a hotel next to it. The “narrative museum” immerses visitors in “the sights and sounds of the slave trade, racial terrorism, the Jim Crow South, and the world’s largest prison system,” according to its website. It draws the connections between the legacy of slavery and the current-day mass incarceration of Black men.

“You walk up to a jail cell and there is a hologram of a person, and the person tells you why they’re in the jail and what happened to them,” Dr. Jackson recalled. With multiple theaters featuring continual showings of movies, there is so much to see and read, that Dr. Jackson and friends spent several hours their first day and went back the next morning to see more.

“It makes the point that our economy would not be where it is if it were not for the support of Blacks and people of color since the inception of the United States, because slaves supported our economy,” he said. “It makes a good argument that they are responsible for where we are. It’s quite an educational experience.”

The sculpture "Exode, No Home" by Sandrine Plante is just one of many exhibits bringing the visitor closer to the reality of slavery. (Photo: Equal Justice Initiative)

But the learning doesn’t stop with the museum and memorial, as he was quick to find out when he headed to the city’s center on his first visit.

“What I discovered downtown was just unbelievable,” he said. “Montgomery has really come to terms with its civil rights past behavior.”

As home to numerous civil rights leaders, the city has become an important stop on the national Civil Rights Trail, a collection of museums and historically significant churches, schools, courthouses and other landmarks that debuted in 2018, not long before Dr. Jackson’s visit. The Capitol Building itself has become a museum with its own significance, as it served as the end point for the third march for voting rights that began in Selma, and was the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “How Long, Not Long” speech.

A block and a half down from the Capitol Building is the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church – a site of mass meetings to organize the famous Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“It’s where Martin Luther King preached – and it’s where he was for the garbage men’s strike and then the bus strike in 1957, which was in response to the arrest of Rosa Parks,” recalled Dr. Jackson. “It started where the entire population of people of color in Montgomery boycotted the buses for two years, and it bankrupted the bus company.”

The city has placed historic markers commemorating important moments in the Civil Rights Movement all over town.

“There’s a spot marked where Rosa Parks got on the bus, and another spot marked where she was arrested and taken to jail,” he said. The site of her arrest for refusing to give her seat to a white man is now home to the two-story Rosa Parks Museum and Library, centered on Rosa’s story and containing a whole children’s wing and a restored school bus, among other artifacts.

Montgomery is also home to the Freedom Rides Museum, a former Greyhound bus station that was the site of the attack on the Freedom Riders, restored to how it looked in 1961; the Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, where the eponymous judge legalized desegregation of buses in 1955; and the Dexter Parsonage Museum, once Dr. King’s home, which was bombed several times during the civil rights struggle, among many other highlights.

Reading about the march that began in Selma and ended at the Montgomery Capitol, the group decided to drive to Selma and walk the Edmund Pettus bridge, where the march began amid police violence in what came to be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Segregation was a bitter fact of life in the United States under the so-called Jim Crow laws until 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. (Photo: Equal Justice Initiative)

You can’t come away from it without being touched,” Dr. Jackson concluded. “The problem is, the people who need to see it won’t go.”

One of the most enjoyable parts of the trip was the interaction with locals, he said. During their walking tour of downtown, they stopped and read a number of historical markers along the way. “There must be at least 10 to 12 placards downtown, written on both sides, so there’s a lot of detail to them,” he said.

Since they were obviously tourists interested in civil rights, several times they were approached by locals who had their own stories to tell. “One told us about the slave market, and why the woman in the fountain is looking away from the Capitol,” he recalled.

Dr. Jackson has been talking to his grandchildren – Jackson, 16 and Shayley, 13 – about what he has learned and plans to teach them more. He’s also encouraged them, and others, to do more educational travel rather than going to beaches and drinking in bars.

“I just enjoy getting inside new things and looking for new places to go to improve my mind and understand what the past has created for us,” he said. “I would say that anyone who wants to know about history and to improve on their minds would enjoy a trip to Montgomery, Alabama.”

Upcoming: Dr. Richard Jackson is the founder of the Mali Nieta Foundation, which he has used to raise funding for educational projects in Africa. He will be taking his entire family to Tanzania in May to celebrate the opening of a library and school for the Masai people – and then they will go on safari. Stay tuned for Part II of Dr. Jackson’s adventures.

Editor’s note: Buzz travel columnist Tracy L. Barnett is a Lowell Thomas travel journalism award winner and longtime travel and environmental writer. Email her at [email protected] to share your own travel tales.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.