All the Advantages

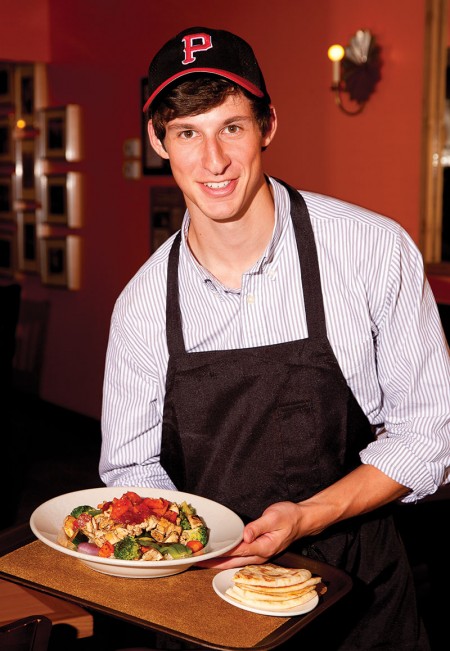

While fewer than one quarter of American teens are employed, a record low, 18-year-old Walker Spier has discovered the satisfaction of earning his own paycheck at Island Grill & Juice Bar in Tanglewood. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

No one likes to talk about money. And people really don’t like to talk about the potential drawbacks of having plenty.

Yet when the Center on Wealth and Philanthropy at Boston College did a survey of the very wealthy (average net worth: $78 million), the respondents had one overwhelmingly common concern: They worried how their money might harm their children.

Most of us don’t have $78 million. Yet we could clearly be considered affluent. The median adjusted gross income in 2009 was $32,396. If your AGI was more than $112,124 that year, you were in the top 10 percent. More than $343,929? The top 1 percent.

Comfortable, privileged, whatever we call ourselves, if we have enough money to live in communities with high-quality public schools, if private school is do-able, if we have college educations and high-status, high-skill occupations, then our children reap huge benefits. Numerous studies have shown that the socio-economic status of a child’s parents is the single biggest predictor of that child’s academic success.

And it’s more than how much we spend. As Jack Kins, a father of two, puts it, financially secure parents “have more capability to do things with their children, to be involved with their sports and to make sure they’re doing their homework.” A recent study shows that affluent kindergarteners have spent about 400 more hours on “literacy activities” than lower-income children.

However, according to Paul Schervish, director of the Center on Wealth and Philanthropy, wealthy respondents in his study worried about their children’s work ethics and spending habits. They hoped their children didn’t become materialistic and that they treated others with kindness and respect.

“Sound familiar?” asks Schervish. “It’s what we all want for our children, though when there’s money, these issues become magnified.”

Christopher and Lisa Zook founded the Houston Select Football League for middle-school boys from a range of backgrounds, including poor families. In working with these boys, Christopher Zook says, “the biggest difference I see in children of privilege is a lack of work ethic.”

Zook, 42, believes having teens work instills that ethic. “There is nothing I like to see more than a young man waiting tables at the neighborhood restaurant to earn gas money, when I know in reality that young man’s father could buy the restaurant,” he says.

The Zooks’ 16-year-old son, Christopher Jr., known as “Caz,” bought his own car using money from a business he started at age 9, placing gumball machines in local restaurants. Last summer, he started a power-washing business to pay for gas.

One disadvantage of growing up privileged, Caz says, “is you might be tempted not to work as hard because you’ve got something to fall back on.”

17-year-old Annie Bernica has discovered the satisfaction of earning her own paycheck at Island Grill & Juice Bar in West University. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

Caz remains friends with his old Select Football teammates. “Some have loads of money; others don’t. Some live with both parents, some have divorced parents, and some don’t live with their parents at all,” he says. “I think we all learn something from knowing each other.”

When Jack Kins was 12, his father, who owned a beer distributorship in Corpus Christi, put Jack to work, starting at 5 a.m., on a delivery truck. “Could you imagine putting a kid on a beer truck like that today?” laughs Kins, 42. But he still remembers when his supervisor mentioned he didn’t have air conditioning at his house. “That was a defining moment for me,” says Kins.

Adam Newar, a father of three, believes financial security can allow parents to be overly involved. “It’s a natural inclination,” he says, “but you have to let them handle things on their own. Less affluent parents don’t have that luxury. They can’t take two hours out of their day to go to school and protest a grade.”

Affluent parents have more time and money to spend on their children – and they use it. Sociologist Annette Lareau, in her book Unequal Childhoods, coined the term “concerted cultivation” for the parenting style she saw in affluent families.

While Lareau noted the benefits of that parenting style, she also noted drawbacks. Affluent kids in her study spent far less time with extended family, felt more competitive with their siblings and were less independent.

To foster independence, Liz and Greg Bernica say they want their three kids to work for what they want, so they required them to pay 10 percent of their college tuition. Their youngest, Annie, 17, currently works as a server at Island Grill.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.