An American in China

China is a land of contradictions. City and country border each other, and the long-standing belief that in order to move forward, you must leave the past behind, is disproved. China’s rapidly growing economy and innovations over the past few decades have been stunning, considering much of the land is essentially mountains and farmland. I got to witness China firsthand this summer. As an American-born girl of Chinese heritage, this trip was not merely traipsing through the East. I got to see the history of my people.

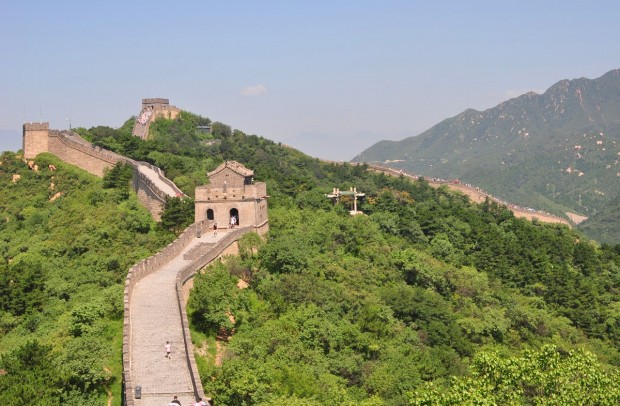

Beijing was our first stop. Our tour group was off to see the Temple of Heaven, Great Wall of China, and the Forbidden City over the next few days. What all three have in common is the Ming Dynasty, the time period in which they were built. To this day, they are still standing even through the turbulence of China’s history.

When I was walking along the Great Wall, touching a wooden column, or facing off with a stone lion, it hit me that these were living pieces of history built over three centuries ago. And I had only seen a fraction of the sights in Beijing; over the next few days we would see more temples, but more importantly, we were going to explore the metropolitan area. For dinner, we explored the brightly lit city and waded our way through throngs of people. Beijing houses 22 million citizens, and that was especially apparent at night. We passed countless stalls with vendors selling souvenirs; hair pins, woven sandals, and carved statues littered their stalls.

It was surprisingly easy to blend into the crowd. My father knew rudimentary Chinese, and he helped us through ordering at restaurants and asking basic questions. However, people would do a double-take when they realized that I did not speak the language. They would switch to English, give me a knowing grin - foreigner! - and send me on my way.

After Beijing, we traveled south to Xian. The most well-known artifact in Xian is not a singular statue, building, or painting. It is an entire army. Excavated from a farm village – literally rising from the ground – are the terracotta warriors that have defended Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor and uniter of China, for centuries. We toured the excavation pits that held the warriors and visited a museum where they recreate the process of molding and firing them in the traditional way. Something interesting I learned about the terracotta warriors was that they weren’t just foot soldiers like I had thought. Among the grey heads were archers, horses, and generals. The wooden chariots and most of the weapons had long since disintegrated, but you can still see their hands and feet in place; it’s up to the imagination to fill in the blanks.

At night, my family split off from the tour group to visit the Muslim Quarter, a long, winding marketplace that is entirely unique since it blends Chinese and Muslim culture. The owners of the storefronts are Muslim and their food is a fusion between the two cultures. For instance, we tried Paomo, a soup of unleavened bread, beef, and noodles. It was like the entirety of Beijing filtered into that one alleyway; there were so many people talking, eating and selling that it was electrifying.

By far, Guilin was the most rural city we visited. Characterized by its majestic mountains, it has been a subject of art for many poets and painters, and printed on the 20 yuan note. A poem from the renowned Tang dynasty poet Han-Yu says, “The river winds like a silk ribbon, while the hills are like jade hairpins.” To enjoy the Guiling mountains, we took a boat tour along the Li River. Our finish line, a small village, used large birds called cormorants to fish for the locals. The boat passed by a line of them, strung by their ankles to a log floating on the river.

The other part of the trip involved a visit to an ancient rice farming hamlet. They were an incongruous sight against the verdant terraces that surrounded them. Built on a foundation of stacked, unmortared stone, their houses were nailed wood and little else. The space below sheltered farm animals. Some of these stilted houses have been around since the Qing dynasty. It seemed like nothing had changed.

Our final destination was Shanghai, a modern, financial metropolis. Like Beijing, the traditional way of life has been preserved and molded seamlessly into the modern world. We visited a silk factory, and got the chance to be taken step by step through the process of making silk, from worm to cloth. It’s a delicate process involving many steps and careful preparation. The silkworms themselves are difficult to care for - their diet consists of only mulberry leaves. But the end product is beautiful even if the steps beforehand are painstaking, just like all art.

After the factory, we stopped by the Shanghai Museum, which was a testament to ancient Chinese art. The most noteworthy exhibit was the bronze vessel exhibit. Wine and food vessels dating back to before China was united were displayed, still intact after thousands of years. Along with the bronze vessel exhibit, other art pieces included the calligraphy, jade, and coin exhibits. This was my favorite part of the trip. Art has always been deeply fascinating to me, and the tranquil atmosphere of the museum was the perfect way to end the eventful week.

The astonishing way China manages to combine technology with tradition was a repeating theme. Something that stayed with me is that change is still possible without having to abandon the past. As a Chinese-American, I always thought that those two identities were completely separate. I now see that two halves make a whole.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.