Heroin Hits Home

Lives lost too soon

Some kids sell lemonade. And then there’s Jonathan Uzick. At the ripe age of 8, he peddled business cards bearing the image of a golden retriever to classmates at Meyerland’s Lovett Elementary, charging $5 a pop. He bartered lessons in the fine art of dragon drawing for a bit of their lunch.

“He was always the entrepreneur, always creative, charismatic, the happiest kid. The first to hug you,” says mom Marcy Uzick. “And empathetic,” laments dad Randy, recalling a text exchange with adult son Jonathan while hunting.

“See anything?”

“I see a little doe.”

“Well, shoot if you want. It’s up to you.”

“He then sends me a picture of him petting the doe,” Randy says. “Jonathan was always trying to save animals, save people. He just didn’t save himself.”

March 1, this year. That’s the day Marcy and Randy’s world fractured into a million tiny pieces. Early that morning they discovered their hazel-eyed Jonathan, 27, dead of an accidental heroin overdose at their Meyerland home, syringe on the bathroom counter, belt cinched around his arm.

He’d helped himself to a bowl of his mom’s chicken matzo ball soup and tossed in a load of wash. This was the day he was to fly to Seattle to find a new job, start fresh.

“The hardest thing I’ve ever had to do was call Robyn. I couldn’t even talk,” says Randy of Jonathan’s twin sister, married just two months prior. Jonathan, all smiles, spoke at her rehearsal dinner.

Marcy made the equally heart-wrenching call to eldest son Robert.

“You know how you sometimes get a paper cut and it hurts real bad, but if the cut is deeper it doesn’t hurt as bad?” offers Marcy. “I think this cut is just so deep that my body can’t comprehend it. My body is desperately trying to protect my heart. It’s not that we’re in denial. We just haven’t processed its enormity yet.”

It’s a lot to process, this scourge of addiction. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), heroin set a milestone, claiming more victims in the U.S. in 2015 than gun-related homicides. It’s estimated that three out of four heroin addicts first used opioid painkillers such as OxyContin and Vicodin. A crackdown on the flow of these prescription pain pills left users seeking the street drug as a cheaper, more accessible alternative.

The result, an unprecedented and deadly heroin epidemic.

“We’re dealing with Jonathan’s death plus having to come to the understanding that he was an addict,” says Marcy. “I probably didn’t use that word to describe our son for two to three months after he died because I was just so shocked.”

Jonathan sailed through Bellaire High School, stellar grades. But a rough patch followed. He moved back to his parent’s Meyerland home after his sophomore year at Texas State University due to poor grades. Then a girlfriend breakup “broke him,” say his parents.

While home, he held down part-time jobs and attempted studies at the University of Houston, dropping out twice. A stint at a psychologist did little to help. “It’s like he didn’t believe in himself anymore,” Marcy says.

Flash forward to early this year, and he’s once again living with his parents for a brief stint, devastated that his new girlfriend moved to Denver without him. They’d originally planned to go together. He’d given up his apartment and job at The Ginger Man pub in Rice Village to do so.

His parents noticed odd behavior. Extreme mood swings. He’d sometimes sleep all day. “I don’t have guilt, but I’m heartbroken that I saw things and didn’t know what I was seeing ’cause we knew nothing about drugs,” Randy says. “His skin looked kind of pasty, eyes dark. We’ve since learned that flulike symptoms come with opioid withdrawal.”

Jonathan’s childhood friends in Seattle proposed that he move there, live with them. They’d help him find a job. He’s game, but plans to visit his girlfriend in Denver before making the move. On Feb. 20, the day before that trip, he settles in for a talk with his mom that stunned her.

“I tried OxyContin last year, but I’m good now. It didn’t make me feel good,” he says of the narcotic.

Marcy feels the blood drain from her face.

“I’ve seen enough of that A&E TV show Intervention to know that if you were on it, you need to go to rehab,’” she replies. “He told me no, he’d go to Denver and be back in a week. I told him I didn’t want to bury him.”

She takes advantage of the week he’s in Denver to find a Houston rehabilitation center with availability. She searches his room, finding no drugs or paraphernalia.

“When he came back he almost seemed like the old Jonathan,” Marcy recalls. But we knew Jonathan well enough to know if he was using he wasn’t strong enough to get over it himself.”

Please go to rehab, they plead. Seattle can wait 30 days.

They found their son the next morning, ashen, on the bathroom floor. They recall the shock, despair. The gut-wrenching phone calls to family.

“I want Jonathan to be remembered for more than his drug addiction. I want him to be remembered for his caring, sweet soul,” says Marcy, recalling a dream where Jonathan came to her.

“He said, ‘I guess I should have gone to rehab.’ And I say to Jonathan, my sweet son, ‘Yes, I guess it’s a little too late.’”

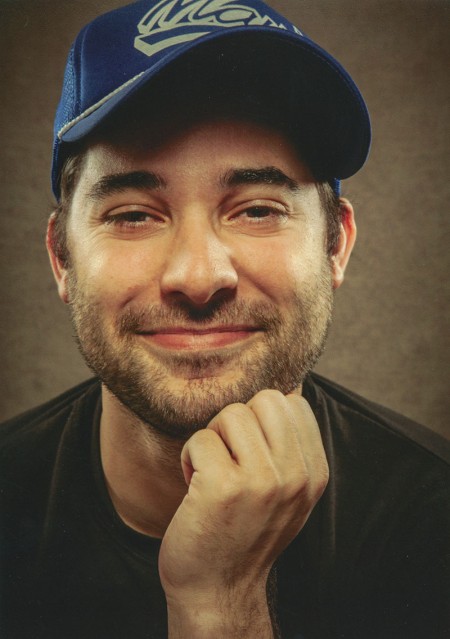

COMEDY LEGACY Harris Wittels’ quirky jokes inspired lots of laughs on the NBC hit show Parks and Recreation and other well-known sitcoms. Wittels died of a heroin overdose on Feb. 19, 2015.

Harris Wittels could land a joke. Table reads among staff at NBC’s hit sitcom Parks and Recreation were gut busting, thanks to the comedian’s quirky, sweetly weird contributions as a writer and co-executive producer of the show.

“He was born funny,” says Maureen Wittels of her son’s fast-track career, writing for The Sarah Silverman Program, HBO’s Eastbound & Down and Parks and Recreation, among other creative exploits. He even coined the word “humblebrag,” writing the book Humblebrag: The Art of False Modesty based on his popular twitter feed of boasts and brags disguised as humble comments or complaints.

“Not many people can claim coining a word that’s now in the Oxford dictionary,” says Maureen, a retired elementary school teacher who lives with doctor husband Ellison in River Oaks. “That was Harris.”

Wittels, 30, was found dead of a heroin overdose at his Los Angeles home on Feb. 19, 2015. He’d performed standup the night before and sent his mom an upbeat email, excited over an imminent move to Manhattan. He was to co-star in the Netflix series Master of None with friend and fellow comedian Aziz Ansari. Harris helped write and produce the critically acclaimed series.

“It’s a living nightmare,” says Maureen, who has found purpose amid the pain through GRASP, an acronym for Grief Recovery After a Substance Passing. She started a Houston chapter of the group to help local families going through such trauma.

Among members of the group, Marcy and Randy Uzick.

“Families need a place to heal and talk about their loved one,” says Maureen, who credits close friend “and rock” Kay Zeidman with helping her find her resolve. “I still have some terrible days, and she’s there every step. I was shocked at how I couldn’t get out of bed on the second anniversary of Harris’s death. Harris loved to laugh. He wouldn’t want me to be so sad.”

Three days before his sister Stephanie’s wedding in March 2013, Harris confided to his only sibling that he was hooked on the narcotic painkiller OxyContin. Don’t tell mom and dad, he said. “I’ve got a great therapist and can handle it.”

He couldn’t.

In early 2014 he came clean to his parents about his addiction and plans to kick it at a California rehabilitation center. At 26, he’d been prescribed OxyContin by a LA hospital after throwing out his back, “probably the beginning of the end,” Maureen laments.

A month-long rehab stint appeared successful at first, with “the old Harris back,” but he relapsed soon after.

Maureen recalls a text to Stephanie later that summer that turned her daughter’s face pale white. “I am on the way to Hazelden,” Harris said of a rehabilitation center in Oregon. “I have relapsed on heroin.”

“I fell to the floor. I lost it. I wailed,” recalls Maureen. “I knew he was going to die. You don’t associate heroin with your child. Heroin is for people who don’t have any money and live under a bridge or steal from their family.”

Maureen didn’t have a good feeling following the Hazelden rehab stint. “I think he was ready to get back to LA and shoot up again.”

It was a sullen Thanksgiving that year with a last-minute text from Harris. He wouldn’t be coming home. Another relapse. “I remember sitting on the couch with Ellison and saying ‘Look, he’s not going to make it. Just start preparing yourself because he’s going to be dead.’”

They flew out the next day, tending to Harris. “A brutal weekend,” she recalls. “He’d been just living for the drug, self-medicating. What it boils down to is I think he was too delicate of a soul to handle this life. He couldn’t say no, he was in such demand. He had to do the drug to feel semi-normal toward the end.”

Yet another rehab, followed by a stint in a sober living home.

Feb. 19, 2015. The day the nightmare came true. “You know what you said was always going to happen? It happened,” Ellison tells Maureen. She falls to the floor, screaming, rocking herself. I can’t do this. I don’t have it in me to do this! She remembers thinking of Stephanie’s young daughter Iris, their granddaughter. “Iris will never know Harris. Harris adored Iris.”

It’s a sunny day. Maureen has opened the sliding glass doors in her high-rise apartment. A faint breeze wafts through, 17 stories up. “I wish I’d see signs from Harris. I just haven’t,” she says. As if on cue, a mourning dove lights on the balcony railing, sits for a few minutes, then flies off.

“Well, look at that,” Maureen says, smiling through tears. “Just look at that.”

Warning signs and finding help

Robert Park, CEO of Houston’s Luna Recovery Services, a private outpatient program, recalls vividly his “dark night of the soul” when inner torment led him to seek help for heroin addiction.

“Some call it the moment of clarity. It’s like windows of opportunity when you see the truth of what you’re doing and have a willingness to do something different,” says Park, 37, whose drug habit included “anything and everything” from age 16 to 24.

“Heroin. It’s like roulette. ‘Okay, am I going to die from this dose or not?’ Especially with the heroin these days,” he says of the street drug often laced with the powerful opioid painkiller Fentanyl and other substances. “Makes it twice as lethal if not more.”

Denial, he says, is always the first battle of the family’s drug war.

“We deal with families all over Memorial, Bellaire, River Oaks and Tanglewood and hear things like ‘Well, we found this in his room, but he says it’s really just the one time.’ They tend to minimize it. I tell them ‘The problem is probably worse than you think it is.’”

Park sees addicts all the time who turned to heroin after first using the painkillers OxyContin or Vicodin. Addiction is chronic and progressive, he says.

For the first time user, if taken orally, the drug can almost seem harmless, Park says. Worry, judgment and the feeling of separation disappear, with some describing a spiritual feeling in early use.

“The user will get a euphoric feeling without the sloppiness of alcohol or other drugs and feels more in control without hangovers. Physical dependence is the result, causing lack of control and separation from those you most care about and self,” Park explains.

Heroin dependence is affecting all populations in America, he says. “It’s become more acceptable and less scary to young adults. We see its prevalence rising in private high schools and colleges.”

Loss of weight and ambition, extreme change in mood or habits, poor hygiene, a raspy, slowed voice, sleeping all day, slipping grades, poor work performance and sneakiness can be signs that something’s amiss. Withdrawal symptoms mimic a cold and the flu.

Googling the Internet for professional help isn’t the best route when in crisis, he explains. Instead, consult friends or other families for referrals. Or go to your family doctor or therapist to find someone with a solid reputation in navigating addiction issues. Luna Recovery and Houston’s Lovett Center, The Council on Recovery, Memorial Hermann’s PaRC, and the nonprofit The Menninger Clinic have solid track records in the treatment of substance abuse, he offers.

(One Buzz resident with a family member who overcame addiction after decades of use recommends the local sober-living community TRT Sober Living.)

If you suspect someone in your home of using heroin, it’s crucial to have the overdose reversal drug Naloxone (brand name Narcan) on hand to block the effects of opiates in the system. It is available over the counter at most Texas pharmacies including Walgreens and CVS.

Overdoses are usually accidental, says E. Vaughan Gilmore, coordinator of Addiction Services at The Menninger Clinic. “Overdose risk can happen when you get a contaminated batch or when they get a stronger dose than you think or maybe they’ve resumed use after a time and lost their tolerance,” she explains. “All these things are a risk for overdose.

“Be vigilant. Don’t simply write things off as typical teenage behavior or ‘They’re just a college student.’ Tune in to warning signs because things can escalate rapidly.”

Family history accounts for some addiction risk, as can anxiety, depression, a stressful household or trauma. Gilmore suggests intervening by expressing concern and empathy rather than hard-core confrontation. “The person already has a lot of shame about their habit.”

Heroin doesn’t discriminate,” she says. “It’s a brain disease. The addiction is so strong physically and psychologically that if people want to use they’ll find a way, and it can include compromising morals and values, like stealing from family members. They’re not bad people. Their addiction is telling them that they need to use.”

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.