Telling Dad’s Holocaust Story

Thanks to puppy walks and a new friend in the neighborhood

What would Millie the beagle and Stelly the schnoodle, two neighborhood dogs who like to play together, have to do with telling a Holocaust survivor’s story? Actually, everything.

Millie and Stelly met in West U last summer, during quarantine, when their humans were looking for a little social interaction.

Millie is Paula and Alan Schlesinger’s third beagle, and she was a happy consequence of social distance. “Our second beagle died in 2019,” Alan explains, “but we said, ‘We’re going to be retiring, let’s wait for that to get a dog, and then wait another year because we’ll be traveling.’ Well, I retired in June 2020. So we moved the dog up and travel back.”

Paula is now a retired pediatrician, and Alan is a retired pediatric radiologist. With a very active beagle. “She follows her nose,” Alan says. “She smells and is off and running.”

Stelly is another happy result of quarantine. Dee Dee Dochen, a marketing and communications professional, adopted the 12-pound, furry Schnauzer-poodle mix about the same time Millie came on the scene.

Puppy walking was a repeat activity for both Alan and Dee Dee. “I’m on Rice, he’s on Lafayette,” Dee Dee says of Alan, who adds, “Our puppies really hit it off.”

“They were completely drawn to each other,” Dee Dee says. “They were so playful, and we got such a kick out of it. While they were playing, we started chatting.”

After a few puppy-instigated visits, conversation turned to What do you do? Alan said he was recently retired. Dee Dee asked what he planned on doing, besides having a puppy.

“I told her I was thinking about writing my dad’s memoir [about surviving the Holocaust], but I was having trouble getting started,” Alan says. “For years, I carried a journal and jotted notes,” he says. “But once I actually retired and had time to do it, I couldn’t get motivated.”

Dee Dee was interested. They talked some more, over the puppies, and she asked if she could read the book when Alan finished it. Four months later, Alan began.

“Really, it was talking to her that encouraged me to do it,” Alan says. “Her interest and eagerness to read it made me feel there are people who want to read this.”

Alan’s original idea was to write his father’s stories for his children and grandchildren. “If I didn’t do it and just told the stories to my kids, and they told them to their kids, with each step there would be more and more lost. I wanted to get it all in a book that I could hand to my kids and they could hand to their kids.”

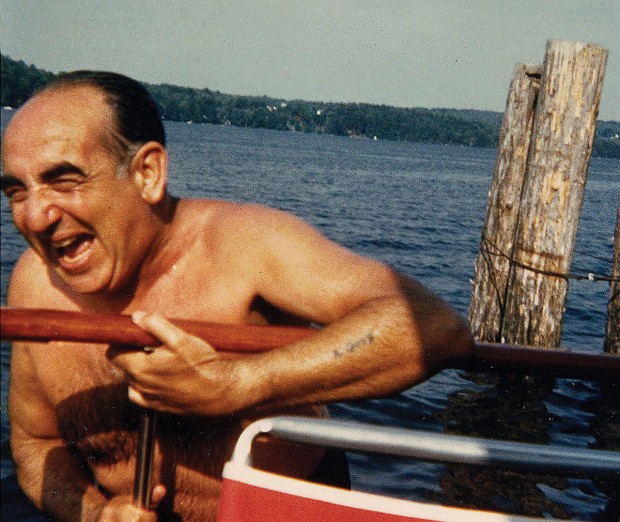

PUPS AND FRIENDS Dee Dee Dochen and Stelly the schnoodle meet Alan Schlesinger and Millie the beagle in the neighborhood for a walk. After the neighbors met walking their dogs and eventually became friends, Dee Dee encouraged Alan to write a book about his father, Joe.

Alan’s father, Joe Schlesinger, didn’t like to talk about his experience. “I asked, but he was very resistant,” Alan says. “Sometime around when I was 20, in the early ’70s, he sat down and told me stories.”

He told Alan that when he was 32, he spent 17 months in a forced-labor camp in Russia. When the Russians pushed the German and Hungarian armies out, Joe, an only child, went back to his parents in Hungary. Still, in just a few months, the three of them were deported to Auschwitz in southern Poland. Joe’s parents died immediately, in the gas chambers, but Joe survived six months at Auschwitz.

“He talked about how his parents were killed, how people were worked to death, and that only the strongest survived,” Alan says. “He felt like he survived because of a combination of good fortune and good instincts, knowing how to be at the right place at the right time.”

As the Russian army began liberating Poland, the remaining prisoners were sent to camps in or closer to Germany. Joe was in that group of prisoners and was moved around to five concentration camps in the span of four months, until he wound up at Nordhausen, a camp in central Germany.

In 1945, three weeks before the war ended, Nordhausen was the target of a nighttime British bombing raid that killed many prisoners and soldiers. Again, Joe survived, and he took advantage of the bombed fences and escaped the camp. He moved west until he found an American displaced persons camp, where he was liberated, and where he met his wife, Perla “Pepi.”

Amazingly, in the displaced persons camp, Joe, who was a doctor in Hungary, volunteered to care for the Nazi sympathizers. “There were three groups of doctors caring for people there,” Alan says. “The American Army doctors cared for the American soldiers, my dad was assigned to care for the displaced persons, and civilian doctors were supposed to care for the German civilians. But the civilian doctors didn’t want to take care of the previous Nazi sympathizers because they didn’t want to be associated with them. They asked the American Army doctors if they would take care of them, but the Army only allowed them to care for soldiers. When my dad heard this, he volunteered to care for the Nazi sympathizers. He said, ‘If they take away my humanity and make me break my Hippocratic oath, then I’m truly defeated.’ He saw this as the beginning of the healing process.”

Pepi and Joe immigrated to America, where they started a family. Joe did a residency in Boston (he had been a doctor in Poland but had to retrain to practice in the U.S.), and then he practiced psychiatry in New Hampshire. In 1969, he moved his family to California, where he went to work for the VA and set up one of the first methadone clinics to treat Vietnam veterans.

He just talked about it that one time,” Alan says. “His philosophy was not to dwell on it, not to let anger run your life. He wanted to celebrate life. So I just knew these stories. They’re stories you don’t forget.

“I kept thinking I was going to get him to write them down, but I got busy, went to college and med school. So those stories had been rattling around in my brain for years. My father died in 1990, and I decided the stories would die with me if I didn’t write them down.” Still, Alan never could find the time or motivation to begin writing, until this year. And he is thankful for the timing.

“Two things made it much better that I hadn’t done it earlier,” Alan says. “In 2010, we moved my mother from California here to live in assisted living, where she lived for the last 5 years of her life. When we moved her, she didn’t want to do much about cleaning the house out, so I said I’d take care of everything. While cleaning out the house, I found a whole bunch of papers, correspondence between my dad and a lawyer in Boston. The German government was providing pensions to people who had been Holocaust victims. My dad had to get a lawyer in the U.S. to deal with the German legal system, and it took several years to get their application approved. So there’s years of correspondence between my dad and this lawyer.

“In the papers, there were all these details, where and when. Now I knew the exact dates he was in Auschwitz and the transport from Auschwitz to Nordhausen. I knew when he got to the American zone. I knew what displaced persons camp he was in. So I had all these details, which was the first big advantage of having waited.

“The second big thing was the internet. I had the details, but I didn’t have the historical context to put them all together. Between those papers and the internet, I filled in a lot.”

Alan spent three months researching and writing Resilience: The Story of How My Father Survived the Holocaust. Dee Dee was one of the first to read it.

“I loved it,” she says. “It’s a remarkable capture of history. There’s so much value of family and friendships among people who had gone through so much together. Alan finishes the book with lessons he learned from his father about life, family, friendships. That’s worth the read in itself.”

Dee Dee asked if she could share Alan’s book with the Holocaust Museum Houston, where she is friends with executive director Kelly Zuniga and board chair Carl Josehart. Within an hour of hearing about the book, Kelly and Carl started working with Dee Dee to share Joe’s story. “This story is unusual,” Dee Dee says, “because you get the after as well.”

In August, the museum hosted a book talk for 70 people, where Dee Dee moderated and Alan told his stories.

“I thought I’d print eight copies, for us and our kids and a few friends,” Alan says. “Everybody who reads it outside my family is like gravy. I’m blown away that more than 200 copies have sold. That’s why I did this – to keep the story alive.”

Alive it is, thanks to Millie and Stelly for bringing inspiration, in the form of a neighbor, to Alan.

“Resilience: The Story of How My Father Survived the Holocaust,” by Alan Schlesinger, is available on Amazon for $4.

Editor's note: Read more stories of local Holocaust survivors here.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.