Flying Colors

When an artist’s headache was a stroke

I think we all wonder occasionally, as we live through our ordinary days, how we’d respond in a crisis and how we would do if (or should I say when?) we are faced with a life-shattering hardship.

Will we rise to the occasion, or will we sink into despair?

Karen Landrigan knows.

Karen, who just turned 60 this fall, has had a happy and fulfilling life: married to her husband, Andrew Adams, for more than 40 years, two grown and happily launched children, Dan and Heather, two grandchildren, Edward, 4, and Lyra, 1, a satisfying career doing graphic design for large corporations, lots of friends, lots of interests. She swam daily, sang in multiple choirs, made beautiful sterling-silver jewelry.

“I’ve always had a lot of energy,” Karen says. “My husband just shakes his head.”

But one day in 2012, when she was 50 years old, right after returning on a 28-hour flight from Kuala Lumpur where Andrew was working, Karen developed a headache that wouldn’t go away and, in fact, kept getting worse.

After a week, she went to see her family doctor, who put her on antibiotics. A week after that, when the headache still hadn’t gone away, her doctor sent her to an emergency room to get a CT scan. “The bad news of this story is the CT scan missed the clot, which was still at that point tiny,” Karen says. “They sent me home with pain meds.”

But a neighbor who had suffered an aneurysm (a bulge in an artery) years before encouraged her not to ignore the still-worsening headache. “It was like a crescendo, just getting worse and worse and worse,” remembers Karen. Ever energetic, though, she continued to swim daily and even hosted a party for 40 the day she called her doctor again. Then, after her morning swim a few days later, she went in to see him. He consulted a neurologist and sent her back to the emergency room for another CT scan. Karen stopped on the way at a Subway (“Because I knew there’d be no food in the ER,” she says), and texted a friend to let her know where she was going.

The friend, Patty Valadka, met Karen at the hospital. It was a good thing she did. Patty is a nurse, and her husband, Alex, is a neurosurgeon. Patty insisted on further testing. The second CT scan showed a blood clot, now the size of a golf ball, in Karen’s brain. She was having a stroke, which is when a blood vessel in the brain is either blocked or it ruptures, interrupting the flow of blood and oxygen, causing brain cells to die. Karen ended up in the neuro-ICU, unable to speak, to understand what others were saying, to read, or to write.

Except for the persistent and severe headache, Karen didn’t have any warning signs of stroke, such as drooping on one side of her face, weakness on one side of her body, or slurred speech. She wasn’t confused, she wasn’t dizzy, her vision was fine. She also didn’t look sick, this fit woman who had just swum 4,000 meters (about 2½ miles) that very morning.

“This is important, nobody talks about it, but a persistent, severe headache can be the sign of a stroke,” says Karen. She makes a point of talking about this whenever she is interviewed, as she often is these days for her art. Karen, who was born and raised in Canada but now lives in Bellaire, spoke of it in 2016 when she was interviewed by a radio station in her childhood hometown of St. John’s in Newfoundland. According to a later story by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), a man named Dennis Mandeville, who had had a headache for 12 days, was listening. Mandeville went directly to a local hospital, where he was diagnosed with temporal arteritis, an inflammation of blood vessels in the brain that can lead to a stroke. The doctors told him that if he hadn’t come in, he probably would have suddenly and permanently lost his sight.

After her own stroke and after 15 days in intensive care, Karen was released.

“And then the misery really began,” she remembers.

Karen still had that inability to use and understand language, which is called aphasia. She had other glitches to contend with as well. She couldn’t remember things, like whether she had eaten dinner. She had some physical problems, including numbness, spasticity, and “drop foot,” which is when the front part of your foot suddenly doesn’t lift up the way it’s supposed to when you’re walking. “I would just fall,” she says.

For 18 months, her recovery and her rehabilitation “ate my life,” Karen says. “I had to relearn to speak, I had to find every word, and I was just very unwell, really sick. It was terrible.”

The headache? She still has it nine years later and probably always will, though it was much worse for the first two years after her stroke because there was still swelling within her brain.

She had nearly died and remains at an increased risk of having another stroke. “It was a near-death experience,” she says. “Your life’s wrecked, there’s no getting out of that, it’s never going to be the same. It’s devastating. There was a lot of crying, a lot of anger with the universe.”

On top of all that, the clock was ticking. The first year and a half after a stroke are considered crucial. That’s when a person is most likely to recover their affected abilities, if it’s possible at all.

Every day, Karen would get up at 6 a.m., sit down at her dining-room table, and do all the homework her speech-language pathologist, Dr. Marina-Elvira Papangelou, had given her, and then some. Monday through Friday, she went to daily speech-therapy sessions. Her oldest brother, Jim, would call her every day, and using materials Dr. Papangelou had sent to him, he would work with her. She’d continue working on her therapy exercises till 11 every night.

She began swimming with her club, Houston Cougar Masters, again 10 days after leaving the hospital. It’s strange what abilities a stroke victim retains. Karen, a lifelong competitive swimmer, could swim – though at first, a worried friend, Taryn Walker, swam near her. Karen could also drive. Stroke victims with aphasia are given cards to present to police officers if they are ever pulled over so the officer knows they have aphasia and are not drunk.

That aspect of aphasia was humiliating, Karen says. Though the victim of aphasia is still “in there,” aware and thinking, when they try to communicate, people often assume they are drunk or otherwise impaired.

Karen’s swimming coach, Greg Orphanides, would think of language exercises for her to do while she swam her laps. “He used to say, ‘Okay, swim three 100s, and each time you come back, you have to tell me five words that start with the letter G,’” she remembers.

She continued singing with her choirs, Houston Masterworks Choir, Rice Chorale, and World Voices Houston. (She has recently also started singing with a choir called Resound.)

“One of the most difficult moments,” Karen remembers, “was when my choir friends came over one day, and the music director of World Voices Houston sat down at the piano and asked, ‘Want to see if you can still sing?’”

“I was like, ‘But what if I can’t?’” she says.

She still could, and the mental rigors of singing – following the director’s instructions, knowing where you were going to start in a piece each time during rehearsal – proved to be very good for her rehabilitation.

But getting her language back was a long, painstaking process. When Girl Scout cookie season started, Karen was determined to buy some when girls came to her door. “I had been a Brownie,” she says. “There was no way I was not going to buy some.” But she had to slowly practice each step of the exchange.

The way she saw it, Karen says, “There were two choices: to not open that door and never speak to people again or to work really hard at it.”

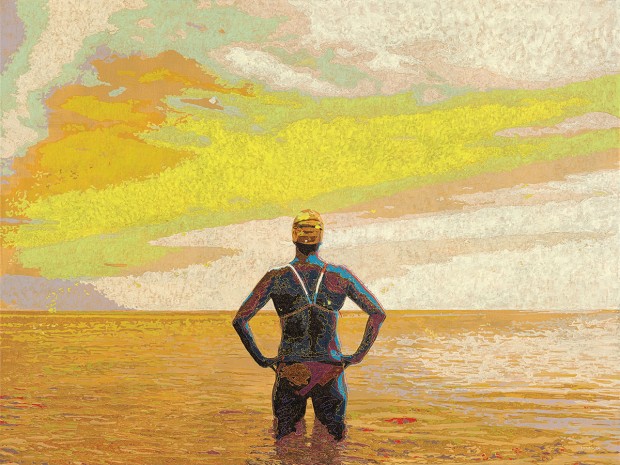

INVICTUS In the aftermath of her stroke, Karen’s childhood band director told her she reminded him of the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley: “I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.” Karen also wrote in an artist note for her newest painting and her largest to date, “There will always be beauty in the world ... We need our fragile flowers to replenish themselves. We need our beauty.” This painting is called “Beauty.”

While Karen had gone to art school and had always been creative, making sterling-silver jewelry and sketching for fun, she had not painted for years, even though people had encouraged her to. But after the stroke, she says, “I started painting because I was really in a bad, dark place.”

Her neuropsychologist, Dr. Cullen Gibbs, told her something she has never forgotten. “It’s a very good, simple idea, which I quite like,” Karen explains. “If you’ve got all these negative thoughts in your head, try to fill your head with something else.”

Her first painting was of her dog, Hugo Bounce.

“And I thought, ‘Well, that was kind of fun,’” she says.

Meanwhile, she had been drawing a swimmer in her sketchbook for years. Now, she sketched that swimmer and “dropped the horizon,” meaning she changed the viewer’s perspective. That swimmer, she saw now, could look like she was about to fly.

“Oh, that’s worth painting, I thought,” says Karen. She went out and bought the biggest canvas she could fit into her car.

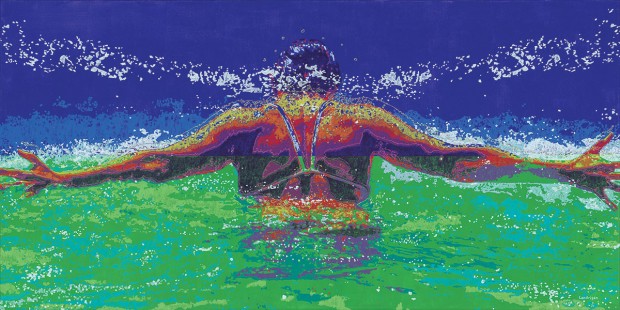

The resulting painting was “Soaring.” It’s of a female figure, swimming, her arm raised midstroke. She is surrounded by water, which is reflecting light.

“She could be flying, she could be dying,” Karen says. She continues, “Sometimes you just have to put your head down and push through the misery. If you just stay still, you will drown. The water, life, will continue, whether you like it or not.”

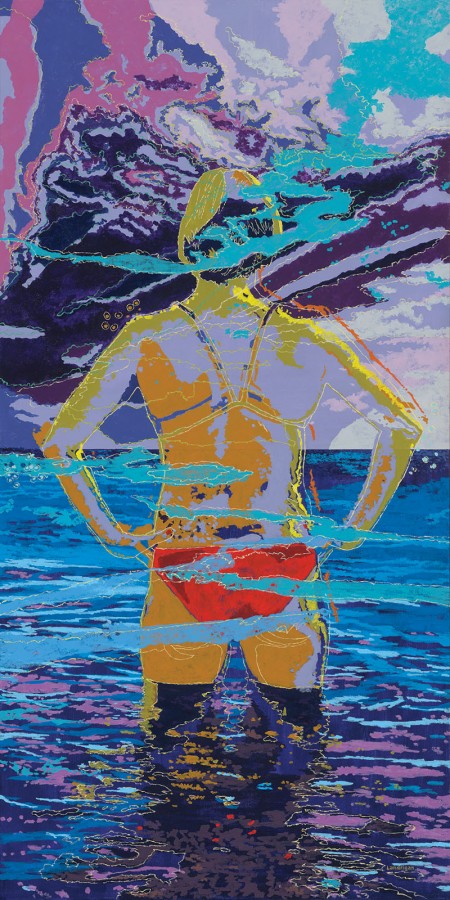

“Soaring” became the first painting in a series Karen calls, “I Have Something to Say.” All of the paintings in the series are of a solitary swimmer and have titles like “Living,” “Rising,” “Persevering,” “Flying,” “Emerging,” and “Standing.” The paintings have won awards, and some of the original paintings, as well as limited-edition prints of them, have been sold all over the world.

PAUSE In her artist note for this painting called "Pause," Karen wrote, "My intermission was unexpected ... I can remain still or put my face back in the water and swim on. That is the only real choice we ever make."

A juror, or art-show judge, who awarded Karen’s painting “Swimming” the top prize in an international competition, said, “Karen’s work is … honestly steeped in the stuff of life: hard, gorgeous, challenging, invigorating, and unifying.”

These days, you would never guess what this trim, stylish, articulate, cheerful woman has been through, but Karen says she still works around the lingering effects of the stroke. She might ask people to write things down for her so she’ll remember. Sometimes, she has her husband write an email for her because it’s quicker. And she still has that headache.

But in her artist statement for the “I Have Something to Say” series, she wrote, “This is what my art as well as my existence is about – whether to fly or die. I choose to fly.”

She’s at work on a new series of paintings, this one called “Still. Life.”

You can see more of Karen’s work at these sites: karenlandrigan.com, landriganart.com, landrigan.redbubble.com, and society6.com/landrigan.

Their lives after stroke

Other survivors of stroke have told their stories, in books and in films. Among them:

Aphasia: The Movie: Karen’s friends from swimming found this movie and watched it to learn more about what she was going through. It’s the true story of an actor named Carl McIntyre, who, like Karen, had a stroke and had to relearn how to speak.

Still Sophie: An award-winning short (7-minute) documentary about Sophie Salveson, a young singer and actress who suffered a stroke at the age of 19, and her battle with aphasia and paralysis.

Both a book and a movie (directed by Julian Schnabel), The Diving Bell and The Butterfly, is the memoir of Jean-Dominique Bauby, who suffered a stroke at the age of 44 that left him “locked in,” unable to move or speak. He dictated his book one letter at a time using the only movement he was capable of, blinking his left eye.

In 2011, 34-year-old Lotje Sodderland, a documentary-film producer living in London, suffered a stroke. After she woke, she started recording videos of herself with her phone because she otherwise couldn’t remember. She used this footage as the basis for My Beautiful Broken Brain, her 2014 documentary about her first year after her stroke, currently available on Netflix.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.