And That’s Margie

Tales of love, loss and laughter

MARGIE’S MEMORIES Author Margie Jenkins, 97, reflects on her third book, I Don’t Remember Getting Old, a candid, witty account of a life of love, laughter and loss. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

Sprinting after a moving bus in sweltering heat, arms flailing, isn’t fun. But if you’re going to fail at the mental arithmetic of bus-chasing, you should at least have Margie Jenkins by your side.

“Mom drove me to the bus every morning to catch my ride to my summer department-store job in downtown Kansas City,” recalls Margie’s eldest daughter, Toby Gilbert, of a decades-old event, hot-seared to memory. “As we got there, the bus pulled away, and we honked, but we knew we could catch it at the next stop. It pulled away quickly at the next, too, because no one got on, so we are honking and driving to the next stop. It pulled away again. And it proceeded like that to where I’m running all the way downtown behind a bus.”

Hair mangled, clothes askew and basted in sweat, her Forrest Gump attempt (Run, Forrest! Run!) at catching public transportation put her in a monstrous mood. “I was hot and mad. I arrived at work looking like I’d been set on fire and left on the side of the road!”

But hunched over the steering wheel in side-splitting convulsions sat Margie, howling in laughter at their cat-and-mouse chase with a bus driver oblivious to his harried followers. When Toby saw her mom’s reaction, she, too, dissolved in laughter.

“And there you have it,” says her daughter. “That’s Margie. She perseveres. She’s positive. She always finds the light.”

SHARING WISDOM Margie Jenkins has authored multiple books; her latest is called I Don’t Remember Getting Old. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

Author Margie Jenkins, 97, sits in a sunlit office in her home, reflecting on grief that swamped her like a murky tide: the 2016 death of her husband, Bob Jenkins, known as Jenks. He was tall, handsome, smart and the owner of Margie’s heart since their high school days in Kentucky. They were married 70 years.

“The loneliness gets to me the most,” Margie says. “I miss him so much.”

But she found the light.

She took comfort in a writing exercise, daily missives to her late husband called Letters to Jenks. “I wrote about anything and everything, as if I was talking to him and telling him about my day,” she says. The cathartic routine morphed into her third book, a heartwarming memoir, I Don’t Remember Getting Old, that spans the entirety of Margie’s life: family vignettes of love and loss; fun times and hardships, all laced together in a breezy, candid style that delights the reader.

“You have to have a schedule and a project,” says Margie, who wrote the book to “remember my life and encourage others to remember theirs. You have to have something to get up for, to keep you moving. It was a great memory jogger.”

Speaking of jogging, no, she doesn’t. But she does exercise daily and is an avid reader. “I don’t walk well, I don’t hear well, I don’t see well, but otherwise I’m perfect,” she quips.

“Her book, to me, is what the world needs now. Margie’s wisdom,” daughter Toby says. “Having survived the Great Depression, the death of a brother in WWII and other things that life brought, she’s the epitome of resilience. With the social upheavals today and the pandemic, it’s great for readers to see how she’s weathered storms and reinvented herself through perseverance. She’s got grit, survival skills and love to share.”

“She’s a force,” agrees Margie’s eldest son, Rick Jenkins. “I hope we are all doing as well at 97. She’s very determined and extremely focused when she gets something in her mind.”

“I think it’s important to have an attitude of gratefulness. And we should all live as bodaciously as we can,” Margie says. “We can be missionaries of happiness. And when things happen that you’re worried about, give it to God. God has a lot of my stuff.”

From an early age, Margie knew what she wanted.

“When I grow up, I will marry a tall, handsome man like my brothers, have two boys and two girls so everyone has a brother and sister, but have them close together so they can all be friends,” she writes in her fifth-grade essay. “All the kids will have chores to do so that they will feel an important part of the family. I am going to live in a white house and have lots of puppies. My family will play together and have lots of fun, and everyone will love each other.”

As if embracing Margie’s wish list, the universe aligned and produced two boys and two girls: first Toby, then Rick, Susan and Bob. And, of course, their beloved German Shepherd, Dana Von Blitzen of Augsburg (who, indeed, had lots of puppies).

“And, yes, we had chores,” says Rick of his Sunday cleaning-dishes routine.

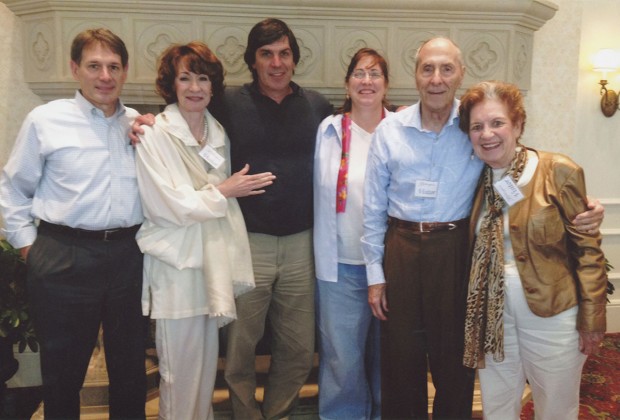

Margie’s longing for a family of two girls and two boys came true, as predicted in her fifth-grade essay. From left: Rick Jenkins, Toby Gilbert, Bob Jenkins, Susan Jenkins and husband Bob “Jenks” Jenkins with Margie. (Courtesy of the Jenkins family)

Jenks’ executive career at ConocoPhillips meant multiple moves. Margie bloomed where planted. “We had just moved from Kansas City to Houston in the late ’60s, and our neighborhood needed someone to help organize the building of a pool for the adults. My mom volunteered,” recalls youngest son Bob. “Did she have any construction experience whatsoever? No. But I have a distinct memory of a guy with a backhoe, and Mom is telling him where to put giant boulders. That’s a pretty good indicator of how she is. She just steps up and does what’s required.”

Neighborhood newbie Margie also baked cookies, delivering them door-to-door to help her children make friends and new connections. “She created a support system for us wherever we went because we knew nobody,” says youngest daughter Susan. “To this day, I don’t have any trouble at all meeting people.”

But life wasn’t just about cookies, kids and puppies. Once the nest emptied, Margie had plans.

The urge to help people is embedded in her DNA, as sure as a handprint dried in cement. As a child, she’d organize family nights with dancing, games and treats to lift moods when things felt heavy. Now she was feeling the pull of graduate school. She’d get her master’s degree in social work.

At the time, a woman of 52 applying to graduate school was a rare occurrence. The University of Houston rejected her application. She insisted on an appointment with an admissions counselor. Nervous, palms sweating, she listened to all the reasons he thought it a bad idea. Could she keep up at such an advanced age? Spots needed to be reserved for “people who can make a difference. And we want to save places for minority students.”

To which Margie replied, “Sir, I am an older woman. I would be a minority student.”

She was accepted.

“I was their token little old white lady in graduate school.”

She signed up for a class to “test my brain skills as an elder student” before facing graduate school rigors. The only course available was Human Sexuality, a class of 999 young college students. And Margie. “I figured I was married and had four kids. I could pass that.”

The class was enlightening. “I didn’t know everything.”

Mid-lecture, seven men, naked except for hats, belts and sneakers, streaked across the auditorium stage, jumped down next to Margie, then ran out the door. The professor asked if anyone was offended. Margie’s hand went up.

“What offended you?”

“There were no women represented.”

The audience erupted into foot-stomping cheers, says Margie, who made an A in the course. She wrote daughter Susan, also in college, to share her academic success. Susan sent her a dollar.

“We kids got a dollar for every A we made during school,” says Susan. “She deserved it.”

Margie stands amid sentimental family possessions, including a portrait of her mother, Mabel Hope Martinis Little, at age 21 and a 1754 rocker handed down to her grandmother. (Photo: Genesis Photographers)

Margie excelled at graduate school, received her master’s in social work and, at 60, opened a private practice, counseling clients, ages 9 to 90. Soon, she’d add newspaper columnist to her accomplishments, writing the column Sixty-Something that addressed topics of interest to older adults, many of whom were facing end-of-life issues.

At 79, Margie penned two books on the subject: You Only Die Once and My Personal Planner, widely revered as expert guides.

“It’s a difficult subject, but the biggest gift we can give to someone we love is to talk about death and write things down, what our wishes are,” Margie says.

She recalls a terminally ill 9-year-old boy who told her, “I don’t have long to live, so I have to live fast.” Margie counseled him and his parents. And the boy, who raised butterflies, made final wishes known: that his parents release his case of cocoons to transform and fly away when he died. “I can still get teary thinking about that.”

Always her biggest cheerleader, Jenks joined in her mission after retiring. The couple produced a DVD and CD called Don’t Slam the Door On Your Way Out, talking to groups nationwide – from the FBI and military organizations to churches and retirement homes – about the importance of discussing humankind’s one collective fate, death.

“As funny as it might sound, we had a great time going around talking about death together. Jenks was so much fun, and he was the perfect person to help share that message,” she says, recalling his sweet words just weeks before he died. “He told me he was so grateful for the amazing life we’d had together and how our marriage was more than he could have ever hoped for.”

And once he died, he told Margie, he wanted to return as a great blue heron, the magnificent bird that cruised over their neighborhood lake with slow, deep wingbeats.

“The day Jenks died, a beautiful blue heron landed in our garden,” she writes in the book. “I knew it was Jenks coming to say he was okay, and I would be okay, too.”

Editor’s note: “I Don’t Remember Getting Old” and Margie Jenkins’ other books are available on Amazon.com.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.