Twisted Logic

The Rubik’s Cube is back

When the Rubik’s Cube, that six-color, three-dimensional, twistable puzzle, first hit the American market in 1980, we were all basically on our own when it came to solving it: twisting the rows and columns of smaller cubes that make up the whole until each side of the puzzle was one solid color. It’s been calculated that a standard Rubik’s Cube can be placed in over 43 quintillion (that’s 43 followed by 18 zeros) positions. Only one of them is correct.

Mine was never solved.

The cube’s inventor, Erno Rubik, a Hungarian architecture professor, wrote, in his recent memoir, Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All, that attempts to do it entirely by “intuition” are usually “doomed.” It took him a month to solve his own puzzle. That makes me feel a little bit better.

But when things come back into fashion – think bell-bottoms and maxi dresses – they are never quite the same as they were originally. And so it is with the Rubik’s Cube and all its descendants, now often referred to generically as “twisty puzzles” since they are manufactured by multiple companies under multiple brand names.

Of course, even back in 1980, some people, including groups at MIT and Caltech, did figure out how to solve the Rubik’s Cube. They developed algorithms, sets of instructions or formulas, that can be used to solve the puzzle.

These days, you can learn those algorithms from YouTube videos. (Google videos on how to solve a Rubik’s Cube and you will get about 590,000 hits.)

That’s not to say that it’s easy. Comments on a popular 10-minute beginner’s tutorial by a Canadian competitive speed cuber called J Perm, include:

“This has to be the most rewinded video on youtube;”

“Me* following every step and actually solving the cube: WHAT IS THIS SORCERY;” and

“Oh, so this is how parents feel when you try to explain new technology to them.”

Joseph DePinho, currently a junior at St. John’s, brought a Rubik’s Cube with him on a family vacation the summer before sixth grade. He gave up and left it on a table. When he came back, it was solved. His cousin had done it but wouldn’t show him how. “I spent about three hours watching videos,” said Joseph. “It’s hard to learn. It requires a lot of focus and determination, but once you do, it becomes easy, like riding a bike.”

He added, “My dad thought I was a genius.”

Eleven-year-old Morgan Norris got a Pyraminx, shaped like a pyramid, as a party favor. “Morgan was instantly hooked,” said his mother, Julia Oh. He went on to learn how to solve a host of these puzzles, including Megaminx (a dodecahedron, which, with its 12 sides, looks something like a sphere made up of flat planes) and mirror cubes, which are all one color, usually metallic silver, but each row is a different height. When a mirror cube is twisted, it changes shape, which makes it even more mind-boggling than a regular cube.

Morgan can solve other “exotic” cubes as well, including the Skewb, each side of which features a square, turned onto its corner, in the center, surrounded by four triangular pieces, and the Ivy Cube, which has curving pieces, two triangular corners and an oval-shaped center, on each of its faces. He can also solve the more traditional cubes.

NEW TWISTS Twisty puzzles now come in a variety of shapes. From left: a Megaminx, a Pyraminx (above), the standard 3x3x3, a 1x3x3 or Floppy Cube, and a Windmill Cube. (Photo: Jenna Mazzoccoli)

The original Rubik’s Cube has three rows of three “cubies,” as Erno Rubik calls them. The edge and corner cubies rotate around a central pivot to which the six center cubies are attached. Those center cubies, therefore, can only rotate. They do not move and are always in the same position relative to each other: the white center, for instance, is always across from the yellow one. This original configuration is now called the 3x3 and is considered the standard cube. But, in official competitions, speed cubers race to solve cubes that range in size from 2x2 to 7x7 as well as some of the exotics. One cube enthusiast even made his own unofficial cube (and then solved it on YouTube) that is 33x33.

Once a cube enthusiast learns to solve a cube, the next challenge involves solving it as quickly as possible – and the times speed cubers achieve seem unbelievable. For instance, the world record for solving a 2x2 (two rows of two) is under half a second. The current world record for solving a 3x3 is less than three and a half seconds.

Sounds impossible, right? In compilation videos of the top five solves of the 2x2 and the 3x3, it looks impossible. (Note: Competitors have up to 15 seconds to examine the scrambled cube before starting.)

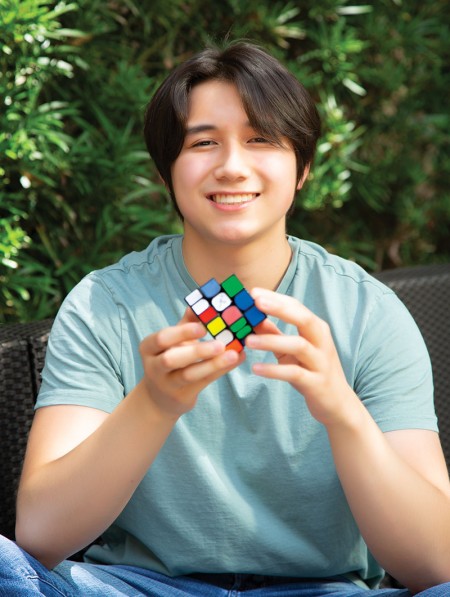

Gabe Kalina can solve twisty puzzles, including the Rubik’s Cube, with impressive speed. (Photo: Dylan Aguilar)

Thirteen-year-old Gabe Kalina is Morgan Norris’s next-door neighbor. The two boys spent an afternoon solving cubes of varying sorts and trying to explain to me how they were doing it. As their fingers flew and their cubes clacked – and they were moving slower for my benefit, mind you – it looked like magic to me.

Gabe brought his first cube to summer camp, and a friend taught him how to solve it. At one point, during the pandemic, he was practicing four hours a day.

This hobby, Gabe said, requires memorization (competitive speed cubers know hundreds of algorithms), rapid pattern recognition, and muscle memory. Both your brain and your hands have to be fast. Gabe showed me how, while most people start by twisting the cube using their whole hand, his much-faster twists involve using just one finger. “I play the piano and that helps,” he said.

The cubes used by speed cubers are different from the original ’80s version. The original Rubik’s Cube was meant to be a toy. Speed was not a concern. The corners of the cubies had 90-degree angles. Speed cubes have rounded corners to make them a little faster. Speed cubers disassemble them and lubricate them with “cube lube.” At the same time, some of the latest cubes have magnets, which can be swapped out and adjusted, inside the cubies, so that, when a speed cuber twists the puzzle, the rows snap into place. “It’s a balance between them being fast but not spinning out of control,” said Zack White, a delegate for the state of Texas with the World Cube Association, and the lead delegate for the Southern United States. “People choose their cubes and adjust them based on their preference.”

A recent development in cubes are ones that are Bluetooth-enabled. An app can then keep track of a player’s moves and times, kind of like the exercise app Strava for cube-solving.

The cubes do not have to be expensive. Zack said you can get a “pretty good” speed cube for $4-10, though some cost $70-80.

The World Cube Association (WCA) is a global nonprofit organization run entirely by volunteers like Zack. It does not run competitions itself. “Literally anyone can organize a competition,” said Zack; the association certifies competitions and makes them official. You can search for upcoming official competitions near you on the WCA website. Some are held in private homes – the last one Zack attended was in a cabin in the woods – and also at schools, universities, community centers, churches, and libraries.

Most of the events at official competitions focus on solving a specific type of cube as quickly as possible, but there are other permutations, including solving them one-handed and solving them while blindfolded.

In “multi-blind” events, players are given one hour to solve a certain number of 3x3 cubes. They are allowed to spend as much of that hour as they’d like looking at the scrambled cubes, but then they must don a blindfold and solve all of them, one after another, without looking. The world record for this event is held by American Graham Siggins, who correctly solved an astonishing 59 cubes out of 60 while blindfolded.

Zack, now 23, was in middle school when he got his first Rubik’s Cube as a stocking stuffer for Christmas. He taught himself to solve it, using a CD that came with the toy, on a road trip his family took the next day. By the next year, he convinced his mother to drive him six hours to Brownsville (“Somehow, she agreed,” he said) to attend his first competition. Zack, who now works in information technology for the city of Beaumont, has attended 78 competitions, including the 2013 World Championships in Las Vegas and the 2019 World Championships in Melbourne, Australia.

The Australian competition is the setting for a documentary called “The Speed Cubers,” now playing on Netflix. It’s about the heartwarming friendship between two top cubers, Australian Feliks Zemdegs and American Max Park.

It was that documentary and the fact that the Houston toy store she works for, Big Blue Whale, began selling Rubik’s Cubes, that got my 25-year-old daughter, Diana Thomson, interested. “I thought if the speed cubers can do it that fast, I can at least solve it,” she said.

Often at the toy store, children will scramble the twisty puzzles on display. “People don’t like to buy cubes that have already been scrambled, even though the first thing they’re going to do is scramble it themselves,” Diana explained. (This probably says something about human nature, although I don’t know what.) Everyone else at the store now knows to hand those scrambled puzzles to Diana.

Zack says that if you can solve a cube at all, you should come to a competition. (Another place to look for nearby competitions, he said, is the Facebook page Texas Speedcubing.) “Going to a competition is so much fun,” he said. “We’re competing and we’re rivals, but at the same time, the atmosphere is very welcoming and encouraging, and we’re all friends.”

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.