Hardcore Parkour

From James Bond to Houston

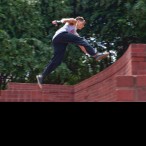

Moore and other parkour practitioners get from one point to another in the most direct route, using momentum to propel themselves in an acrobatic way. (Photo: stpimages.com)

Franklin Moore was the kid balanced on the top of the playground dome or crawling on the wrong side of the monkey bars.

Now a senior at Bellaire High School, the 17 year old is still climbing. Every week, he heads to Hermann Park or downtown to Tranquility Park to scale walls. He jumps from them and bolts over them. He’s in constant movement, running along narrow ledges, sliding under obstacles, jumping from a high wall to a lower planter, dashing across and vaulting from the benches.

He’s not a daredevil – well, maybe he is, but he’s not looking to injure himself. Along with the scrapes and bruises, he’s getting physically and mentally sharper.

What Moore does is called “parkour.” Maybe you’ve seen it on a viral video or in a James Bond movie.

“I started because it looked really cool,” he said. “And it felt really cool, the things I was able to do my own body. It’s a great workout, and it takes my mind off of life, my problems.”

Parkour practitioners get from one point to another in the most efficient – and often the most acrobatic and impressive – way possible, using momentum to propel themselves while remaining safe.

“Parkour is a way to adapt to your environment using only your body. It’s the idea of getting from one point to another in a creative, ‘survivorish’ way,” said Cameron Pratto, executive director of Urban Movement, which offers parkour classes at Studio Fitness in the Heights, as well as in Clear Lake and Spring.

After seeing parkour in the James Bond movie Casino Royale four years ago, Moore took a class at Houston Gymnastics Academy and did parkour with a neighbor, who soon lost interest. Now, he does it alone.

“It’s taught me how to approach a problem from lots of different angles because in parkour there can be one obstacle where you can do several different moves to get over it or several different things to just play around on that object,” he said. “That applies to life, too, because if you come at a problem straight on and keep trying to do it the same way over and over, it’s probably not going to work out.”

Supposedly developed in France 25 years ago, parkour is a sport for people who often aren’t into traditional team sports. Practitioners – a male is a “traceur,” a female a “traceuse” – compete only against themselves, striving to get better while exploring a city.

Sure, sometimes walking from point A to point B is the most efficient way, Pratto said. But what happens when a wall or other obstacle is in the way? Parkour teaches people to figure out what fears are stopping them from scaling that wall (a fear of heights, perhaps?) or jumping from this roof into that window (a perfectly reasonable fear of breaking bones or missing the window) – and how to create strategies to overcome the obstacle and the fear.

Kyle Moses, 14 and a freshman at The Emery/Weiner School, was intimidated by a Kong vault, which involved launching himself over an obstacle horizontally, then propelling himself back up into the air with his hands so that he cleared the obstacle. His coaches sensed his hesitation, so they asked him to go through it step by step to see what was making him afraid. Then, they had him go through each move slowly until, in a week, he had a good grasp of the move.

Some parkour practitioners are all about impressive, flashy style seen in YouTube videos. Then there are those who practice a more introverted style that focuses on finding a balance within themselves, testing their limits, emphasizing stealth movement.

When Kyle wanted to sign up for parkour classes, his parents were hesitant for safety reasons. After several months, his dad said Kyle is in the best shape of his life, and he’s suffered only some scrapes and bruises. Kyle said he has introduced friends to the sport, but some have found it just too intense.

Andrea Kawaja, a 38-year-old insurance agent/office manager, remembers how her muscles ached and she was running out of steam during quadrupedal movements – crawling on her hands and feet without her knees touching the ground. She struggled to reach the finish line. But the others, about 75 in all, yelled encouragement and slowed their own pace to match hers, giving her companionable motivation to continue on.

“I kept panting and crawling, and finally I screamed a primal roar that gave me the energy I needed to push on those last few feet,” she said. When she was done, the others patted her on the back.

Mars Suleymanova grew up doing competitive swimming in Russia and was on the Ohio State University synchronized-swimming team. She’s always been good at athletics. But with parkour, she struggles to perfect the movements. “Before something works, it doesn’t work about a million times,” said Suleymanova, a 26-year-old translator. “It teaches you very quickly what you can and can’t do, despite what your ego might tell you.”

That step-by-step progress is what makes parkour attractive, she said.

“I needed to feel like I’m getting better at something every day, even if it was just a little bit,” she said. “It’s really a mental thing. I needed to learn some patience. I needed to have humbling experiences, which parkour definitely is. It hits on all my faults.

“In your day job, the only real gauge of growth is adding zeros to your paycheck. That doesn’t really say very much about how strong of a person you’re becoming and whether you’re working on yourself. Parkour shows you definite progress mentally and physically.”

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.