Mandy's Miracle

A one-in-5.7-million heart

MIRACLE Against all odds, Mandy Nathan received a successful heart transplant in November and was discharged from the hospital in December. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

Across the globe, people have been coming to terms with a new reality: maintaining a six-foot distance between other human beings, scheduling happy hours via Zoom video conference, venturing out only as far as their own backyards.

It’s a strange time, to say the least, but it’s one Mandy Nathan knows all too well.

The 52-year-old lawyer and former Bellaire mayor pro tem spent more than six months stuck inside a hospital, without a single breath of fresh air. Her reality was one that, even now, as the coronavirus pandemic forces many of us to self-quarantine, is difficult to imagine.

Mandy, a natural leader who comes across as friendly and down-to-earth, suffers a genetic heart defect that caused arrhythmias and mini-strokes for several years. She ultimately faced heart-failure symptoms and was put on the heart transplant list last June. One hundred seventy-three days lapsed while Mandy awaited a heart in Houston Methodist Hospital.

When she finally did get a viable donor heart – a statistical miracle, it turned out – the only place Mandy wanted to go was home.

“People always said to me, where do you want to go when you get out, and I’d say I just wanted to go home,” said Mandy, dark-haired and slim. “I just wanted to sleep in my own bed and sit on my couch and out on my back deck. Just the normalcy of it all is wonderful.”

According to guidelines from her doctors, Mandy’s first three months with her new heart were to be spent primarily at home, for the risk of infection was high. When she did go out, for a doctor’s visit or a walk in her neighborhood, she was instructed to wear gloves and a mask.

As soon as Mandy hit that three-month marker, coronavirus took center stage, and she was forced to take even greater precautions, neither leaving her home nor having friends come over for afternoon visits.

It was disappointing, she admits. Just when she was ready to return to semi-normal life, Mandy was instead forced into an even greater state of isolation.

And yet, Mandy’s experience of spending 206 days in the hospital has left her and her family with a changed mindset. They remember the gift that is simply waking up each day.

When the instinct is to complain – for instance when Mandy is taking what feels like the 800th pill for the day – Mandy’s husband David pipes in with: “You know what doesn’t suck? Having a heart.”

“It might be trite, but we do have a tad bit of perspective here,” he says. “The world might be going up in a pandemic, but we had our own personal crisis and managed to get through it. So in a way it feels like, if everyone just does their part, hopefully we can get through this one too.”

In 2013, David was in morning advisory at St. John’s School, where he works as an upper school English teacher, when he got a call from teenage son Zach.

Zach explained over the phone that his mom was acting strange. She was unable to get her words out and was “not right.” David instructed his son to immediately call 911 while he rushed home from school.

Mandy Nathan takes her first breath of fresh air after spending more than six months in the hospital. (Photo: Michael Gilbert)

What Mandy was suffering that day was the first of several transient ischemic attacks (TIA), also called a mini-stroke. Mandy was generally healthy but had dealt with smaller heart problems since age 21, when a doctor discovered during a typical checkup that Mandy had supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). Although it causes a rapid heartbeat, SVT is usually not dangerous and did not affect Mandy’s daily life. In 2006, the SVT developed into atrial fibrillation, a more significant heart-rate abnormality that can increase one’s risk for stroke.

Still, it wasn’t until the TIA that Mandy’s life was disrupted. For Mandy, the TIAs manifested as temporary bouts of hampered vision, unclear speech and restrained movement of her limbs. At first, Mandy was put on medications.

But when she suffered repeated mini-strokes over the next couple of years, doctors implanted a cardioverter defibrillator device in her chest. The implant helps control arrhythmia by delivering an electric shock to bring the heart rate back to normal when it is out of rhythm.

Even as Mandy recounts her medical history, making her way to a low point in 2018 when she told her cardiologist, “I feel like I’m going to die,” her sense of humor is evident. Her narration is peppered with witty commentary – for instance, that the genetic heart defect she was ultimately diagnosed with after thorough testing in 2018 is supposed to cause heart failure or arrhythmias, but, of course, with her luck, she got both.

She easily throws her head back for an unrestrained laugh, finding the bits of humor in a situation that could easily drive one to depression. During her stay in the hospital, Mandy’s wit persisted through CaringBridge, an online journaling platform where patients can share their health journeys with family and friends.

Mandy’s posts were filled with anecdotes and musings about life in the hospital. Each post was titled with the name of a song or a pop culture reference; one is named, “Have You No Sense of Decency, Madame, at Long Last?” (referencing the McCarthy hearings) and focuses on Mandy’s “hospital induced lack of dignity.” She speaks openly of the extra-large hospital gowns that “don’t cover what they should,” her “potty situation,” and, in a paragraph she instructs the gentlemen to skip, an uncomfortable pelvic exam.

A pervasive undertone of the posts is that Mandy is on the verge of “beating the system,” for instance, when she managed to sneak a refrigerator into her room or when she got the entire resident staff to implement “Mandy’s Rules,” which dictate no waking her up before 6:30 a.m. for protocol check-ins.

Of course, there were times in the hospital that Mandy felt down.

“There were days I wanted to just not get out of my bed, but you’ve got to make yourself, and you have to believe that what happens is God’s plan,” said Mandy, who, both naturally and purposefully, opts for positivity.

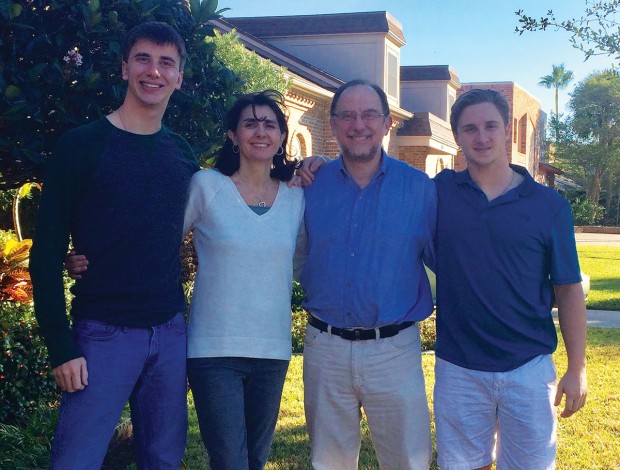

She says her faith, along with a strong support network of family and friends, helped her get through the most difficult days. Along with her husband David, Mandy’s two sons Zach, 23, and Max, 21, visited their mom when they could. Max, who studies at Tulane University, spent the summer in Houston, lifeguarding at the Bellaire pool, while Zach was interning in Houston before starting a graduate accounting program at Rice in the fall. Mandy’s parents, who live in Galveston, also made weekly visits.

Some of the most challenging days, when Mandy most needed to lean on friends and family, came just weeks before she finally got a heart.

When Mandy was first put on the heart transplant list, she underwent a series of protocols aimed at reducing her antibody levels. While antibodies typically help us fight off infections, high levels reduce the number of donors from whom one can receive a heart. Mandy’s levels were unusually high. Even worse, none of the typical protocols seemed to be working. After receiving multiple plasmapheresis treatments, intravenous immunoglobulin treatments and a regimen of chemotherapy drugs – all of which have their own set of uncomfortable side effects – Mandy’s antibody levels were still too high.

Mandy’s doctor came up with one other possible treatment he discovered after scouring the research. That treatment had worked on one other patient, all the way in France, and it was a last-ditch effort. If this eight-week treatment plan didn’t work, it was unclear what would come next.

“Before that [treatment], we would always point to a Plan B or a Plan C the doctors had,” says David. “There was always something else. This really was kind of the last thing. We really didn’t know what the back-up plan was going to be after that.”

By this point, Mandy found herself asking questions like: “Why in the world is this happening to me? What if I don’t get a heart? How long will they let me just hang around in the hospital waiting for a match?” The alternative to a heart transplant is typically a mechanical pump called an LVAD, but those increase the risk of stroke, which Mandy’s condition already put her at risk for.

She started thinking about everything she would miss if she did not survive the ordeal: her sons’ graduations and weddings and children, the years with her husband. She felt overwhelmed knowing that her passing would cause immense grief for her family and friends.

Mandy shared this earnestly while beginning to tear up. A long-time attendee of St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, Mandy says her faith taught her to take one day at a time instead of worrying about the future.

“A Bible verse I recited several times was Matthew 6:34, which says, ‘So do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow brings worries of its own. Today’s troubles are enough for today.’

“I don’t sit in my room thinking that God has forsaken me,” Mandy wrote in an Oct. 15 entry on CaringBridge. “I’m not afraid of dying, and I’m clinging – more tenuously at some times than others – to the knowledge that God is walking and suffering along with me on this walk, and that whatever His plan for me is the right plan.”

Getting to that point of acceptance involved deep conversations about heaven and prayer with family, her best friend Julie Ellerbrock and with the Reverend Brian Gowan, senior chaplain for spiritual care and education at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Mandy’s ultimate rock was David, who says his role was to be the “voice of unreasonable optimism.” A natural at making others laugh, David, upbeat in disposition, was always steadfast in his assurances to have faith.

Whether he was in denial or simply too busy to think of all possible scenarios, David says he never really thought about the possibility that Mandy might not make it. Throughout Mandy’s stay at the hospital, David continued teaching at St. John’s, while visiting the hospital as much as possible.

“When all this is going on, you’re just trying to get the laundry done and keep your head down and get your [work] done,” David says. “I really wasn’t planning for any inevitabilities. If you did that, you couldn’t get what you needed to get done each day.”

Around 11:30 p.m. one Saturday in November, David got a call from Mandy. He prepared himself for the worst – Mandy never called with good news late at night.

What he got instead was the greatest and most improbable update he could ask for: Mandy was getting a new heart.

“The last thing in the world I was expecting was good news,” David says.

For several weeks prior, the focus had been on getting Mandy’s antibody levels down. Nobody would have expected doctors to find a match.

By all accounts, the donor heart was a miracle. Reverend Gowan recalls the “m-word [miracle]” circulating the halls for days after Mandy’s successful transplant surgery.

TOGETHER Mandy says her husband of 28 years, David Nathan, was her rock throughout her transplant journey. Finally back at home, Mandy now enjoys simple moments with David – relaxing in the backyard, watching television, dinner at the kitchen table. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

David later found out that statistically, the odds of finding a match were one in 5.7 million, a number so small it’s impossible to fathom.

“They never said those numbers aloud,” said Mandy’s friend Julie. “They just kept saying it would be rare. But when you hear those numbers, it’s staggering. It’s one of God’s miracles. That doesn’t just happen.”

Mandy expresses deep gratitude for her donor, whom she doesn’t know too much about. She knows the donor was a young woman from another state. And she understands that while the heart was the greatest gift she could ever receive, it was simultaneously another family’s greatest loss.

Today, Mandy is back home, spending much of her time walking, reading and catching up on television shows. Physically, she feels strong aside from back pain and minor side effects of medications. “If it weren’t for my back, the day I walked through my front door I would’ve said I felt almost completely back to normal,” she said.

Mandy suffered a back fracture just days after her heart transplant surgery. The steroid drugs she was on while undergoing the antibody-reduction regimen gave her osteoporosis, increasing her risk of fracture. It was a simple twisting motion – to slide out her tray for a meal while in her hospital bed – that caused the fracture.

For her new heart, Mandy will continue to take a host of medications, including three anti-rejection pills; each year she’ll visit the cardiologist for an annual biopsy.

“Usually how long your new heart lasts depends on age, general health and response to the transplant, all of which play in my favor,” she says. “That said, it is never far from my mind that things can go wrong at any time, so I’m living each day with that in mind.”

This year has been one of uncertainty for much of the globe; each day seems to bring a new update on the spread of the coronavirus, and none of us knows whether our lives will go back to how they were, or if a new normal will persist post-pandemic. For Mandy, those uncertainties and doubts are amplified a hundred times over.

Thus, while sequestering herself to her home, Mandy enjoys the small things – sleeping in instead of being woken up by the sound of a medical machine, lounging outside with her two cats, binge-watching television series like The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel with David.

“Thinking you’re going to die or have to accept a heart that might render you disabled definitely gives you a new perspective on life,” Mandy says. “Every day is a miracle, and I’m grateful for every one.”

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.