Full Circle

Bracelets to remember our soldiers

The bracelets are cuff-style. They come in a number of colors and can be made of a number of materials: silver, stainless steel, aluminum, copper. They are engraved and go by many names, depending on their exact reason for being: memorial bracelets, KIA bracelets, POW/MIA bracelets, hero bracelets.

They have been used to commemorate police officers killed in the line of duty, victims of terrorist attacks, victims of domestic violence. But most of all, they are used to commemorate members of the military: those killed (KIA stands for “killed in action”), captured as prisoners of war (POW) or missing in action (MIA).

They all started 50 years ago this Veterans Day, on Nov. 11, 1970. That’s the day the first Vietnam-era POW/MIA bracelets, made by a group of California college students to raise awareness of the missing soldiers’ plight, went on sale, for $2.50 each. When the college students’ group, Voices in Vital America (VIVA), stopped making them six years later, there were almost 5 million bracelets for the Vietnam POWs and MIAs in circulation.

(In 1973, 591 of the POWs were brought home in Operation Homecoming. According to the National League of POW/MIA Families, 1,586 American soldiers are still considered missing in action and unaccounted for from the Vietnam War; 99 of those are from Texas.)

When Senator John McCain, who was held as a POW in Vietnam for 5½ years, died in 2018, people filled social media with photos of their bracelets with his name on them. One of the people who wore a John McCain POW/MIA bracelet was Bob Dole, the senator and decorated World War II veteran.

When McCain became a senator in 1983, Dole pulled him aside to show him his bracelet, a moment both men later described as emotional. In turn, McCain also wore such a bracelet, in memory of Matthew Stanley, who was killed in action in Iraq in 2006.

Bellaire resident Mary Ann Reed had one when she was 12 years old in the 1970s. “It had a huge impact on me at the time,” she says, “that the man whose name was on my 12-year-old wrist was suffering from horrible torture.”

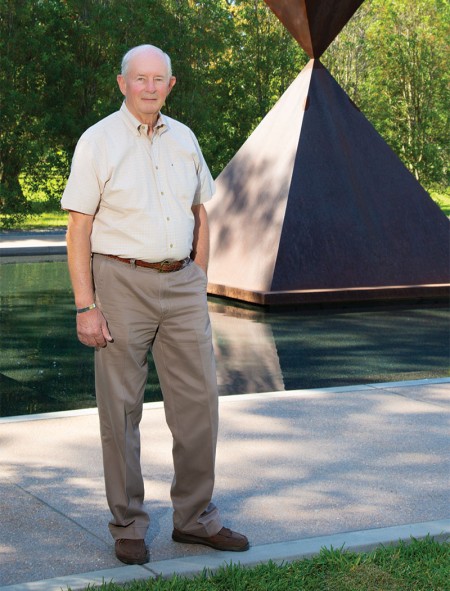

Lt. Col. Tim Ayres was a prisoner of war for 11 months during the Vietnam War. He still receives POW bracelets with his name on them. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

She was recently reminded when, looking for things to do during the pandemic, she went through a box of childhood mementos her mother had sent her four years earlier. Among the many items in the box, including caps she had worn on teeth she had chipped as a child, was the bracelet for Lieutenant Carroll Beeler, who had survived.

“The internet is fabulous,” says Reed, who googled his name and came up with his complete biography. Beeler, who became a captain while in the military, did come home, but died in 2003, at the age of 59, when the jet he was test-piloting crashed. Reed, again through the wonders of the internet, was able to track down his daughter and give her a call. “She was kind and polite and said I was more than welcome to send the bracelet back to her,” says Reed, “but honestly, it probably freaked her out a bit that I could find her.”

The idea behind these original POW/MIA bracelets was that people would wear them until “their soldier” came home, and many people then sent theirs to their soldiers or to their families, when their remains were found. Capt. Beeler received many, and his father, before his death, answered each sender personally. Another Vietnam POW, from Houston, Colonel Thomas “Jerry” Curtis wrote personal letters to over 500 people who had sent him his bracelets after his return, according to his biography, Under the Cover of Light by Carole Engle Avriett.

Tim Ayres, who retired from the Air Force Reserves as a lieutenant colonel in 1995, still gets bracelets sent to him. An alum of Bellaire High School and the Air Force Academy, Ayres was shot down in Vietnam May 3, 1972, at the age of 27, and held prisoner for 11 months.

Ayres refers to himself as “a short-timer” because some of the POWs spent almost nine years in captivity. For that 11 months, he was listed as missing in action, “which is the worst for the families,” he says. “They knew I had been alive on the ground but didn’t know what had happened to me after that.”

He had not known about the bracelets, until, upon his return, hundreds of people sent their bracelets to him. To this day, he still receives four or five of them a year. The latest one arrived just last week.

“I give people an option,” he explains, “because sometimes they’ve grown attached to the bracelet. I tell them that, if they would like to keep it, they can, or I would gratefully accept it.”

Early on, the Air Force or the Department of Defense would send him the contact information of people inquiring about him, and he would contact them. These days, with the internet, he gets emails, letters and the occasional phone call. His latest bracelet came from a daughter, who, cleaning out her mother’s house, found it in a drawer. “Her mother had bought all her children bracelets at the time,” says Ayres.

AMERICANS REMEMBER Lt. Col. Tim Ayres, an alum of Bellaire High School, (pictured here outside Houston's Rothko Chapel) was held as a prisoner of war for 11 months during the Vietnam War. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

If your soldier is still missing, “keep it – and wear it – if they are not home yet,” says Karoni Forrester of the National League of POW/MIA Families. Forrester’s father, Capt. Ronald W. Forrester, was declared missing in action in 1972, when she was 2, and remains missing.

The P.O.W. Network maintains one of several databases of biographies of those missing. The organization will not give out contact information for the soldiers or their families but will forward bracelets on to them, says chair Mary Schantag. She points out that many of the surviving Vietnam POWs are now in their 80s and 90s and so may not be up to responding.

The P.O.W. Network does keep a “Love Letters” page on its website for people who want to reach out. The Virtual Wall, virtualwall.org, an online representation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., which includes those missing in action, can also accept messages and even photos. “Every once in a while, I do look,” says Forrester of her father’s page on the virtual wall. “You may not get an immediate response or even a response at all, but it is a way to reach out to the families.”

ALWAYS IN HER HEART Maddi Armstrong's son, Sgt. Graham Woody, died at the age of 26 seven years ago. (Photo: lawellphoto.com)

Maddi Armstrong, who just retired from being a second-grade teacher at Mark Twain Elementary, did wear a Vietnam-era bracelet. But she now wears another one “every minute of every day,” which she will never take off, for her son, Sgt. Graham Woody, who died in a training accident at Fort Bliss in 2013. He was 26 years old.

Graham, who was in the Corps of Cadets at Texas A&M University, where he earned his degree in engineering, could have joined the Army as an officer but decided to enlist instead. “He wanted to start at the bottom and work his way up,” Armstrong says. “He thought it would make him a better officer.” Just four days before he died, he had been promoted to sergeant. “And he had won numerous awards, too,” said his mom. “I didn’t know about any of that until after.”

His friends from the Army, who call themselves his brothers, had bracelets made and sent her some. They wear them as well. “It fills my heart with love that people are wearing his bracelet,” Armstrong says. “As a mom, I worried that people would forget him. His friends are now in their 30s and are getting married.” She likes that they can look down at their wrists, see his name and think of him. “Every once in a while, I will get a message from one of them that they were just thinking about Graham.”

Just recently, Armstrong’s daughter and Graham’s sister, Heather, was stopped by a man who had seen her bracelet. It turned out that the man, who had been stationed at Fort Bliss while in the military, had met Graham and knew about his death.

Like Graham’s friends, people in the military do often wear bracelets for their fallen friends. One former member of the military said any jewelry store near a military base has the materials and can make them. They are also available from online companies, such as Memorial Bracelets, which started by making bracelets commemorating the victims of 9/11, Steel Hearts, for service-academy graduates, and The Battle Zone. Many of these companies donate part of every sale to veteran and survivor groups. Sometimes, entire groups, including the graduating class of a military academy or certain types of military personnel, such as Army Rangers, will all wear these bracelets.

There is no hard-and-fast rule about the colors of the bracelets, although black is usually reserved for those who were killed. Forrester of the National League of POW/MIA Families says silver or green may signify “missing in action” because green is the color of hope. Mary Schantag of the P.O.W. Network says red usually means the Vietnam War, blue the Korean War, green World War II and gold the Gulf War. Mary wears eight bracelets. “I have a nice little rainbow on one arm,” she says, “and people often stop me to ask about them.”

That may be the most important point. Forrester always asks for the story when she sees someone wearing one. These bracelets are a reminder of what the military does and the sacrifices its members and their families make.

Editor’s note: In the print version of this story, we mistakenly wrote that Bob Dole had passed away in 1996 (we meant that he served in the Senate until 1996). We sincerely regret the error.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.