Spotting Beauty

Spring wave of color delights Houston birders

Sara Bettencourt and Carl Nooteboom both love birding. Here, they’re at the Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary. (Photo: forsythefotography.com)

Along the Gulf Coast and into Houston, spring migration is “extraordinary,” said Sara Bettencourt, longtime bird watcher and Buzz resident. “It’s hard to believe that it really happens every year.”

Nearly 2 billion (yes, with a “b”) birds migrate through Texas each year. In the spring migration, which is at its peak in Houston in late April and early May, the trip north across the Gulf of Mexico leads to a dramatic finish on the upper Gulf Coast.

The migrating birds reach land after flying hundreds of miles without stopping to eat or rest, many crossing the entire Gulf of Mexico in one endless flight. Even tiny hummingbirds make this journey. They arrive exhausted and hungry, so they immediately “drop” to recuperate, creating a bird-watchers’ paradise on our doorstep.

“Spring migration always finds birders struggling to nail down the perfect adjectives for what you see – breathtaking, awe-inspiring, stunning – but really all of those words fall short,” said Sara. “I don’t think the words have been invented yet.”

Because of its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and its position in the central flyway, Houston is a crucial resting area for migrating birds, said Berri Moffett, conservation specialist at Houston Audubon and a Texas master naturalist.

“In the fall, birds making their way south stock up on the food they need to make it across the Gulf without stopping,” Berri said. “In spring, the birds are on their way north to their breeding grounds, and they land in our area after their intense travel. Because the birds are so focused on refueling, and because the timing of spring migration is so much more condensed than fall migration, it is an ideal time for birders to encounter and enjoy hundreds of species.”

(Keep an eye on the latest bird-migration forecast maps and real-time results online at birdcast.info.)

Sara Bettencourt's "spark bird," which sparked her love of birding, was a painted bunting. (Photo: Greg Lavaty)

Bird watching has become a shared joy across four generations of Sara’s family, a commonality nurtured by her parents and now embraced by her siblings, nieces, nephews, and even elementary school-aged great-nephews. Sara, 62, and her husband, Mark, 63, joined the nonprofit conservation society Houston Audubon more than 30 years ago, soon after Sara saw her “hook,” or “spark,” bird.

“Every bird watcher has a bird that gets you hooked on bird watching,” Sara said of the moment she declared herself a bird watcher.

In July 1989, Sara was staying at her parents’ vacation home on the Frio River in Leakey, Texas, about 100 miles west-northwest of San Antonio, where a bird feeder sat outside the window with a pair of binoculars available for viewing from indoors.

“I was sitting on the couch and noticed a bird had landed, so I picked up the binoculars,” Sara said. “I screamed.”

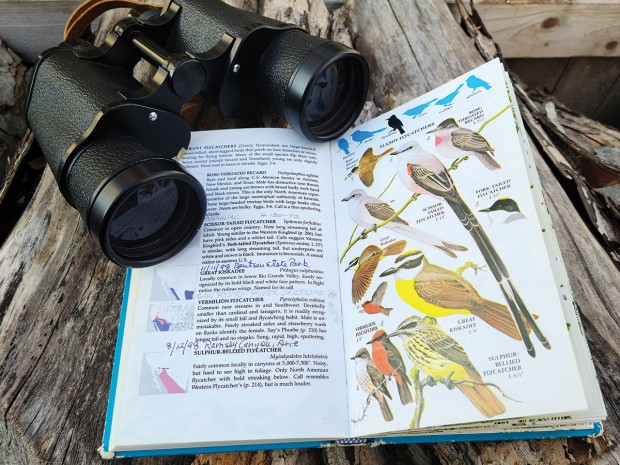

Sara's father, Clint Morse, kept detailed notes in his field guide. Here, he captured the date when he saw a scissortail flycatcher.

Everyone rushed to check on her to make sure she was alright, which she was, of course. But her life had changed.

“It was a painted bunting, and it was shockingly beautiful,” Sara said of the boldly colored blue, green, and red male bird. “That was it. Bird watching became my No. 1 pastime.”

Since then, Sara has documented her sightings of more than 600 species cataloged by the American Birding Association (ABA). Through the years, she has noticed how bird watchers each approach the hobby in their own way, making birding a truly personal experience.

“I’m on a quest to see 700 ABA birds now,” said Sara of her current goal. “One of my good friends has a goal to see more species in Harris County than the year before, another aims to capture photos of additional species, and another takes videos.”

She recently met two women who travel on bird-watching tours to admire the creatures in their natural habitats, but they do not record their observations or even yearn to learn the species’ names.

“Everyone has a different take. If someone enjoys seeing a flock of birds fly over or a red bird at a feeder, that’s enough. You are appreciating birds,” said Sara. “You don’t have to achieve some standard of excellence to be considered a bird watcher.”

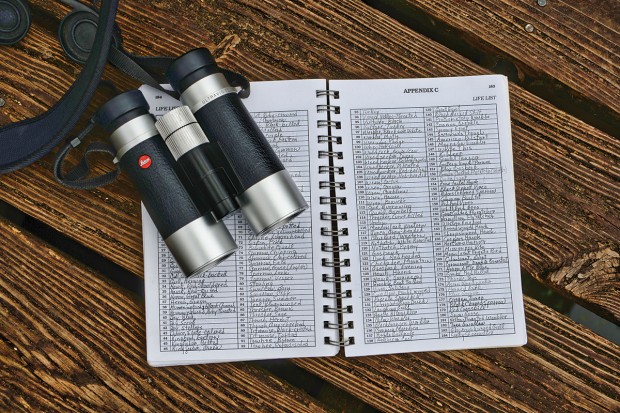

Sara's life-list journal so far has more than 600 birds classified by the American Birding Association. Her goal is 700. (Photo: forsythefotography.com)

At age 5, Sara was with her father, a Houston-based lawyer, at a family cabin in Hockley, Texas, about 40 miles northwest of Houston. He drew her attention to a scissortail flycatcher, identifying the species by name. This is her first memory of birds, and the scissortail flycatcher remains one of her favorite species to spot. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology describes the slender and stout bird with a long, forked tail as “pale gray with blackish wings and tail and salmon-pink flanks and under belly.”)

“Mom and Dad encouraged all of us in the family to appreciate the natural world. As I got more into bird watching, specifically, then so did they,” Sara said.

Her parents, Clint and Mary Frances Morse, have passed away, but her family carries on the legacy. Sara’s son Mike lives in Tuscon, Arizona, and began his birding outings as an infant with his parents. At age 10, his team of young birders even captured first place in the youth division of the Great Texas Birding Classic. He continues to enjoy spotting and identifying birds.

Sara’s brother Clint Morse and his wife Vivian, retired attorneys, and their family enjoy watching birds arrive at their feeders outside their home on the Guadalupe River in Hunt, Texas, 80 miles northwest of San Antonio.

ON A QUEST Sara Bettencourt and Carl Nooteboom share their love of birding while walking through the woods at the Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary in Memorial, one of 17 sanctuaries maintained by Houston Audubon. (Photo: forsythefotography.com)

Sara’s sister Allison Ryder and her husband Dan travel with their family to Galveston from Kansas City, Missouri, to attend FeatherFest, organized by the Galveston Island Nature Tourism Council, during spring migration. Allison’s son, Stuart Ryder, a veterinarian in Kansas City, started birding as a young boy and has “a natural talent,” Sara said. Allison’s daughter, Sara Taylor, and husband Nathan have two boys, Sam, 11, and Ben, 7, who keep bird lists already featuring more than 80 birds.

(The 19th annual FeatherFest: Birding & Nature Photography Festival is April 15-18, 2021. Visit galvestonfeatherfest.com for more information.)

“Birding is really a family thing,” Sara said. “It unites us all. It has gotten in our bloodstream and stayed. I know Mom and Dad would be so tickled that their great grandsons are bird watchers and that they’re interested in the beauty of nature. The fact that it’s birds is just icing on the cake.”

At the home of Buzz resident Carl Nooteboom, birds have been a source of entertainment, intrigue, and solace through the events of the past year – from a global pandemic in 2020 to the life-halting Winter Storm Uri in February.

Carl Nooteboom is chair-elect of the Houston Audubon Young Professionals Council. (Photo: forsythefotography.com)

“When everything was closed, and the only thing to do was get outdoors, or when the power went out and I could only look out the window, I appreciated their presence more than ever,” Carl said.

His children, Michael, 6, and Nora, 5, engage with his hobby every day. He tests their knowledge with pop quizzes each time a bird – such as a cardinal, blue jay, or chickadee – arrives at the feeder outside their window at home. When around town, they ask him the species of every bird they see in nature.

“I love that they show interest,” Carl said. “I’m able to teach and share my hobby with them.”

Carl, 37, serves as chair-elect for the Houston Audubon Young Professionals group, which hosts educational and social events for young adults. Like Sara, Carl had a moment of revelation that launched his bird-watching journey. His “spark” bird was a duck.

Carl Nooteboom watches out the window of his home with his children, Michael and Nora. They quiz each other on the names of frequently seen Houston species, like sparrows and cardinals.

“I've always appreciated birds but didn’t consider myself a birder until my interest was sparked by a duck that frequented the retention pond outside my window at work,” said Carl, who works as an engineer. “I found it odd-looking and wanted to know what kind it was, so I made a sketch and some notes about its markings.”

His mom, Janis Nooteboom, a former librarian, owned the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, which he borrowed in his pursuit. The bird he drew had a bright pink bill with white patches on its wings.

“I felt a sense of accomplishment when I positively identified it as a black-bellied whistling duck,” Carl said. “After that, I bought my own field guide and binoculars and have been keeping a ‘life list’ [a collection of all of his sightings] ever since.”

Carl likens birding to hunting or fishing in the pursuit of a positive identification.

“It's a rush of excitement followed by intense focus, observation, and appreciation,” Carl said. The experience “culminates in either a sense of satisfaction, when making a positive identification, or a desire for more, if it moves out of sight before you can determine what it is. The challenge is what keeps you coming back.”

Since record-keeping began, more than 600 species have been recorded by bird watchers in Texas alone, with more than half of that number representing migratory birds, according to Carl.

READY Michael and Nora Nooteboom watch at the ready for a visitor on their bird feeder. Spring migration brings millions of transitory birds to our doorstep as they traverse the Gulf of Mexico in a nonstop journey, then land on the Texas coast before traveling through Houston.

“Some of my favorites to spot in spring migration are the colorful songbirds – buntings, tanagers, warblers, and vireos. Hummingbirds and various water birds also pass through and are worth keeping an eye out for,” he said.

Several years ago, Carl participated in his first Birdathon competition, a self-guided event hosted by Houston Audubon each spring that challenges participants to spot as many bird species as possible during a 24-hour period.

“My teammate and I spent the entire day visiting several sanctuaries all over Galveston,” he said. “By the end of the day, we had identified more than 100 species, many of which were new to me and could be added to my life list.”

Participants elect their preferred 24-hour window and register online at www.HoustonAudubon.org. The 2021 Birdathon birding period began March 22 and continues through May 7.

The wildlife sanctuaries along the coast see the highest population of migratory birds; there are 17 Houston Audubon bird sanctuaries in Houston. (Read about The Rookery at Smith Oaks Sanctuary, one of four sanctuaries in High Island, Texas, in Cindy Gabriel’s April 2021 story.)

But you don’t need to travel an hour or more to enjoy this annual phenomenon. Forested preservations in Houston also serve as convenient and mesmerizing birding locations (see below for suggestions).

Sara Bettencourt's father Clint Morse's binoculars are a cherished family heirloom. Sara's entire family carries on her dad's legacy and love of nature.

And, you can always entice birds to you. Water drips, bird feeders, and native plants all serve to make birds feel welcome.

“The majority of my birding is from watching the feeder and bird bath outside my window,” Carl said. “Don’t get discouraged if birds don’t show up immediately after you hang a new feeder. It will take some time for them to find the new food or water source. Once they do, it is likely they will return, and other birds will notice. Over time, the amount and variety of visitors will increase.”

To help you identify a bird, Carl recommends a set of binoculars (which he says are a “get what you pay for” type of item and worth the splurge) and a field guide. His favorite field guide apps for download are eBird, BirdsEye, and Merlin Bird ID, all of which pull descriptions from the Cornell Lab’s database. Merlin even allows you to upload a photo you’ve taken to quickly identify using artificial intelligence.

“Bird watching is a great way to connect with nature. Once you start taking notice, you’ll realize they are everywhere.” Much like art, Carl said. “Art is all around us, but we often walk past without noticing. It’s when you stop to appreciate it that you begin to notice the fine details, differences, and beauty.”

Birding in the city

The Greater Houston area has countless spots for you to sit a while or stroll in the woods and observe the migration in action.

At the Edith L. Moore Sanctuary in Memorial, home to the Houston Audubon headquarters, 197 species of birds have been recorded on the eBird hotspot, including 39 species of warblers.

“We also host tanagers, buntings, grosbeaks, thrushes, sparrows, blackbirds, finches, and flycatchers,” said Berri Moffett, conservation specialist at Houston Audubon and a Texas master naturalist. “The creek attracts wading birds like herons and egrets, and we have several raptor species, including nesting owls. My spouse and I saw our ‘lifer’ rose-breasted grosbeak, a scarlet tanager, and a Baltimore oriole here in April 2018, and we can’t wait to see what 2021 delivers.”

Be sure to track your findings in eBird, where other birders can learn what birds are active in the area. In the app, you can see others’ sightings and set up alerts for any rare birds in your area.

- Edith L. Moore Sanctuary: 440 Wilchester Blvd.

- Houston Arboretum: 120 W Loop N Fwy.

- Russ Pitman Park & Nature Discovery Center: 7112 Newcastle St., Bellaire

- Hermann Park: 6001 Fannin St.

- Bear Creek Pioneers Park: 3535 War Memorial Drive

- Smith Oaks Rookery: 2205 Old Mexico Road, High Island, TX 77623

Did you know that?

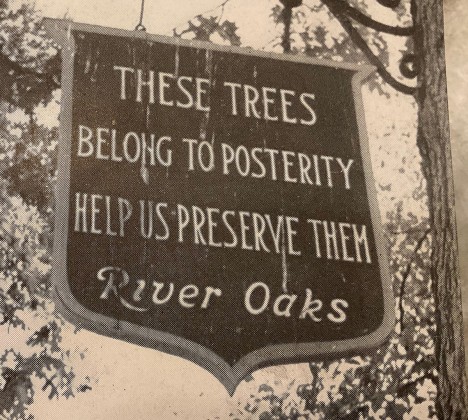

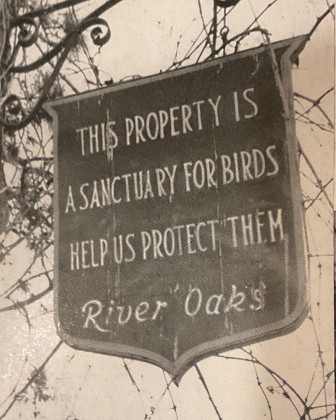

• When River Oaks was developed in the 1920s by the River Oaks Corporation (and founders Will and Michael Hogg and Hugh Potter), the community was intended to co-exist as a residential area and a bird sanctuary, according to the commemorative book River Oaks Eighteenth Year, published in 1941.

• During migration season, the Houston Audubon’s “Lights Out for Birds” initiative – reminding Houstonians to turn out their lights at night – is especially important. Most migratory birds travel at night and rely on the moon and stars to navigate. City lights can disorient birds, making their journey more difficult and lead to building and window collisions, a leading cause of bird fatality.

• Texas Parks and Wildlife recently honored Houston with the title of “Bird City.” The certification recognizes Houston as a leader in community action and bird conservation.

• Birds are a useful indicator of the well-being of an environment. They’re sensitive to change, so an imbalance in an ecosystem can be quickly identified by a sudden departure of native birds.

• Landscaping with native plants is one of the best ways to establish a bird-friendly habitat.

• When Ian Fleming was at his home in Jamaica and writing his soon-to-be-famous spy stories, he needed a name for 007, his main character. Fleming was a bird watcher, and as he looked around the room, his eye fell on his field guide: Birds of the West Indies by James Bond.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.