One Brave Man

In the context of his times, a Fourth of July exercise

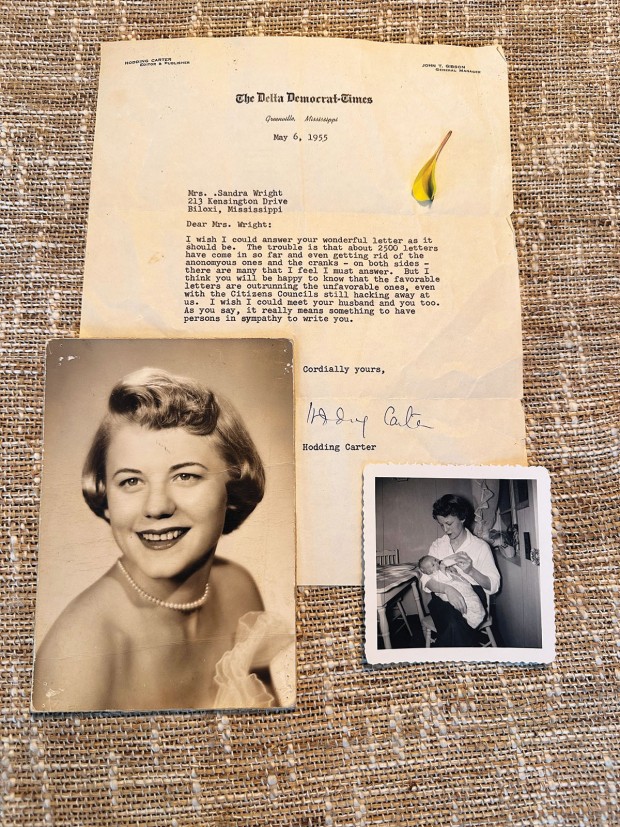

This spring I was rummaging through a drawer of loosely organized family pictures when one folded, yellowed letter emerged. It was dated May 6, 1955, on Delta-Democrat Times stationary in Greenville, Mississippi, addressed to my mother, Sandra Wright, from Hodding Carter (Jr.), the editor.

Hodding Carter Jr. was well known by then in Mississippi and beyond. In 1946 he won The Pulitzer Prize for writing a series of articles that addressed various forms of racial and religious intolerance, including the internment of Japanese Americans following Pearl Harbor.

From this letter to my mother from 1955, it appears that Carter sparked a controversy closer to home. Apparently, my mother was among some 2500 others who wrote to Hodding Carter Jr., and one of several he chose to write back to personally.

I would have been around six months old on the date of this letter, my mother, only 20. We were living at her parents’ home in Biloxi, Mississippi while my father served in the army overseas in Korea and Japan. We would be reunited later that year in Rosenberg, Texas where my parents would take over a small family newspaper, the Fort Bend Reporter. (My father and I didn’t meet until I was nearly a year old.)

In the meantime, my mother, also a journalism major, was clearly keeping up with the news. In May of 1954, the year I was born, the Supreme Court ruled, in Brown v. Board of Education, that public schools must no longer be segregated by race. To put it mildly, this did not go over well in the South, least of all Mississippi.

Two months after that ruling, in a private home in the Delta town of Indianola, Mississippi, a group of white segregationists gathered to form the first “Citizens’ Council.” By then the extreme violence attributed to the Ku Klux Klan was becoming unpopular even among white southerners. The Council’s intent was to reinforce segregation in a more organized, non-violent way, such as evicting black residents from their homes, or removing them from their jobs, in lieu of lynching. Their crimes could be simply signing any kind of civil rights petition, being listed as members of the NAACP, or registering to vote.

While the Klan was considered more blue collar, the Citizens’ Council promoted an image among the business elite, country club types that drew community leaders, politicians, judges and clergy. The Citizens’ Councils spread like wildfire throughout Mississippi and most other southern states. Whites who were critical of their views were targeted as well. They were socially ostracized, and if they had businesses, they were boycotted.

This went doubly for newspaper editors, like Hodding Carter Jr., who dared to call the Citizens’ Council “The Uptown Ku Klux Klan,” in a 1955 article which appeared nationwide in Look Magazine. This prompted the Mississippi legislature to censure its Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist by a vote of 89 to 19.

On April 3, 1955, (one month prior to his letter to my mother) Mr. Carter followed up with a front-page article titled “Liar by Legislation,” in which Mr. Carter reverses the charge as follows:

By a vote of 89 to 19, the Mississippi House of Representatives has resolved the editor of this newspaper into a liar because of an article I wrote. If this charge were true, it would make me well qualified to serve in that body. It is not true. So, to even things up, I herewith resolve by vote of 1 to 0 that there are 89 liars in the state legislature.

By this time, Hodding Carter Jr. was used to receiving death threats and calls to boycott his newspaper. His son, Hodding Carter III, who became the editor of his father’s newspaper in the 1960s, said his father once famously heard a car backfire while eating with friends at a restaurant and told everybody to hit the floor. Living with the knowledge that he could be shot any minute had taken a toll on his nerves.

There is a southern American story in the three generations of Hodding Carters. The first Hodding Carter was a respected member of the community despite his membership in the KKK. His son, Hodding Carter Jr., was willing to risk his life and livelihood poking and prodding against the notions of white supremacy – although not a believer in forced integration based on Brown v. Board, calling himself “a gradualist.” Finally, his son, Hodding Carter III, emerged in the 1960s as a full-fledged champion of civil rights, editor of his father’s newspaper, writer for PBS, and the Assistant Director of the State Department under the Jimmy Carter administration (no relation to the president).

My hope for this and future Fourth of Julys is that we continue to tell these stories of heroes – their courage, their progress and redemption, even if painfully gradual. As Martin Luther King famously said, The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Happy Independence Day.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.