Resounding Resilience

The Deaf embrace life in a hearing world

By nature, preschoolers squiggle and giggle. They’re little balls of energy, limbs constantly moving as if pulled by invisible strings. But this day, at the Melinda Webb School – the Texas Hearing Institute’s preschool for children with hearing loss – they’re laser-focused on the classroom’s visiting author.

Because the author, Alex Narcisse, is like them.

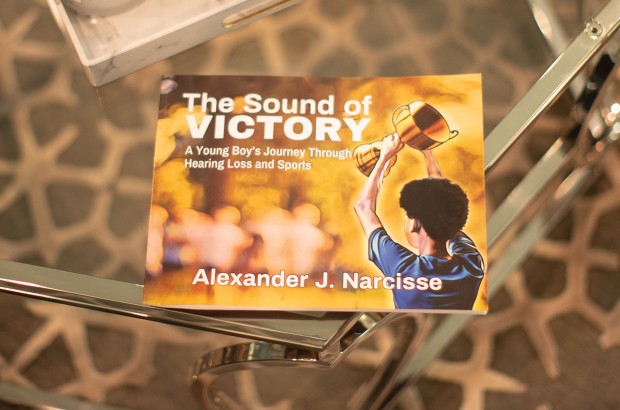

“Always reach for the sky because there is no limit. Follow the story about a young boy named Alex with an unbeatable spirit who was born with hearing loss,” Alex, 16, intones, reading from his autobiographical picture book The Sound of VICTORY: A Young Boy’s Journey Through Hearing Loss and Sports.

“Alex wears cochlear implants to help him hear,” the Bellaire teen recites to his rapt audience. “Alex plays as many sports as he wants because there is no stopping him – not even being deaf.”

The Strake Jesuit junior loves the skill involved in lacrosse, his favorite sport. (Photo: Dr. Victor Narcisse lll)

It was a special reading for the author, for it was within these walls at the Texas Hearing Institute that he started his journey to listen and speak at 18 months of age. He dedicated his book to the organization.

Born with mild to moderate hearing loss, which got worse over time, he required hearing aids by 15 months. By age 2, he was fitted with a cochlear implant in one ear. By 7, his other ear demanded one.

With his cochlear implants, he became assimilated into the hearing world via electrical stimulation of the inner ear. But first, rigorous training was involved to decipher sounds and understand speech, an arduous process that trains the brain to recognize language and its nuances. No small feat.

Alex doesn’t communicate via American Sign Language, but it’s an interest. “I think it would be great to learn,” he says of an online course he hopes to take with his mother, Holly. Approximately 90 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, according to current statistics. Neither of his parents are deaf. His brother, Ethan, 12, has no hearing issues either.

The honor-roll student, mainstreamed in school since the age of 4, begins his junior year at Strake Jesuit this fall where he plays lacrosse. He has set his sights on becoming a doctor, like his father, Victor, or possibly a lawyer, like his mother.

Lacrosse stick in hand, Alex is fully focused, intent on bringing his best on the field. (Photo: Dr. Victor Narcisse lll)

It’s important that young children with hearing loss don't miss out on life’s offerings, he says. Meet life on its playing field and pursue your goals. “You can do anything you set your mind to.”

Alex certainly has. He’s played tennis, baseball, basketball, soccer, rugby, martial arts, and football. He’s hit the slopes skiing and likes to swim. These days, his favorite thing in the world is lacrosse. “I love the physical contact and how it’s a sport that’s not about luck. It’s about skill.” He played for an elite traveling lacrosse team, the Shred Thread, this summer.

Meeting a deaf player with Rutgers University’s acclaimed lacrosse program was quite the inspiration, says Alex. His mom reached out to the player, Campbell Sode, after finding him during a Google search. “I was looking for someone for Alex to look up to who also had hearing loss and played lacrosse. I messaged him and we did a Zoom with him and then he happened to be coming here about a month later, so we met up,” Holly said of Sode, now a lawyer.

“Just meeting him encouraged me to pursue what I want to do,” Alex says. “It was a real inspiration for writing the book.”

Alex read his book, Sound of VICTORY: A Young Boy’s Journey Through Hearing Loss and Sports, to a rapt audience of preschoolers at the Melinda Webb School at the Texas Hearing Institute. (Photo: Dylan Aguilar)

A Facebook group for parents of deaf children that his mother belongs to was also impetus for the creative endeavor. “My mom would tell me about all these parents. Their number one question was always, ‘If my kid is deaf, can he play sports?’”

With his parents’ encouragement – and a bevy of action shots his father snapped of him over the years – Alex got to work. Various special effect tools were applied to give the book’s pictures an artsy flair. And his mom suggested using onomatopoeia words throughout, to help the reader “hear” the action, making connections between the action and the sound.

Fair to say, this might’ve been the author’s favorite page to recite…

POW! Kaboom! Jab! Lacrosse is Alex’s favorite sport. Can you hear the CLANG when the ball hits the crossbar?

In addition to reading to students at the Melinda Webb School, he participated in local author day at the Children’s Museum Houston and did a virtual reading for students at St. Joseph’s School for the Deaf in Indiana.

“He’s such a great role model for other children who are hard of hearing. He really demonstrates the possibilities and outcomes that they can have if they work hard and set their mind to it,” says Kasie LeBlanc, Director of Education with the Texas Hearing Institute. Alex was a volunteer with the organization’s Project Talk summer camp this year, helping assist with activities.

“He’s really mature and wants to give back to the Deaf community,” LeBlanc continues. “That’s what’s so cool about his book. All these little preschoolers are watching him, and I was able to say ‘Look at Alex’s implant. It’s just like yours!’ They were like ‘It is! It’s like mine!’ For them to see an older child with hearing loss is powerful, to see all that he does.”

LeBlanc, formerly an educational liaison for the institute, often went to classrooms, explaining to teachers how to offer support. Typically, hard of hearing students receive preferential seating and access to teacher’s notes if needed. A Bluetooth device that connects the teacher’s voice directly to the cochlear implant is often helpful, too.

“We call it the invisible disability because it’s really hard to see the struggles that the children go through every day, to see how hard they have to work,” LeBlanc says. “In that previous role, I did a lot of training for mainstream teachers, and I would always tell them that hearing aids and cochlear implants aren’t like glasses. When you put on glasses, it fixes things automatically. You see everything you couldn’t see. But it takes a lot of work for these children when they first get their cochlear implants to learn how to listen. Their brain has to figure out what all these sounds are. And every day they still have challenges, understanding nuances of language, dealing with background noise.”

Self-advocacy is a crucial skill for the deaf to learn, she adds.

“Oh, we could write an entire book on self-advocacy!” says Holly. “It’s sometimes a struggle.”

Places with background noise, where lots of people are talking at once, are difficult for Alex. It’s best for a person to tap him on the shoulder to say something, rather than assume he can hear and keep track of those conversations, Holly explains.

Hailey Sutin doesn’t let her deafness define her. The seventh grader at Emery/Weiner brings agile moves to the school’s soccer team.

Alex’s pet peeve is when people think they must get in his face to repeat and over-enunciate words. “If I ask someone to repeat it, that’s one thing. But I like to be just treated as a normal person.”

Hailey Sutin, 12, can relate to Alex. The seventh grader at Emery/Weiner would love to write a book about her hearing loss for an eighth-grade passion project in the future.

She has a cochlear implant in each ear but struggles to keep up in group social environments.

“Sometimes I can’t hear them and then they say, ‘never mind’ if I ask what was being said,” Hailey says. “I don’t press them sometimes to see what the conversation was about. Talking to a person in a one-on-one setting is much better. Also, school group projects are harder for me.”

Like Alex, Hailey loves sports. “The girl has no fear,” says her mother, Leslie, a reading interventionist at Condit Elementary. Indeed, Hailey is happiest tumbling through life in her competitive gymnastics program, curly ponytail flying. She also participates in soccer, volleyball, and track.

Hailey and Logan Goodman, friends since they were babies, are all hugs and smiles at a gymnastics meet.

“We were on the same gymnastics team for like two or three years and Hailey’s really good,” says friend Logan Goodman, 12, of West University Place, a student at Annunciation Orthodox School. “I would be afraid to do something that I’ve never done before, and Hailey just goes and does it and makes it look so easy. She is really good at floor and vault. Bars, too. Beam is hardest, but she’s good at all of them. We do a lot of the same kind of sports in school. She likes soccer and volleyball and track, too. She’s a pretty fast runner.”

Logan and Hailey have known each other since mere babies, just a few months old. Their moms are childhood friends. Logan is keenly aware of hardships Hailey encounters, and feels protective of her, like a sister.

She recalls a gymnastics trip to Disney World, where one of Hailey’s cochlear implants quit working. Logan held Hailey’s hand, navigating her through a suddenly much quieter world. “She couldn’t hear. But she was fine and handled it like a pro and went with the flow. I love having her as a friend. She’s really nice and happy, but I know sometimes it’s hard for her.”

Hailey’s mom is her staunchest advocate. Born prematurely at 25 weeks, her dad’s wedding band fit around her wrist. Twin sister, Sari, died at two months due to an infection. Worried that Hailey also had an infection, doctors started her on the medicine gentamicin. “They strongly believe that it was the gentamicin that caused her hearing loss,” Leslie says.

Her mom sees Hailey’s struggles. “Having cochlear implants doesn’t make hearing perfect. I think it’s sometimes hard for her to self-advocate for herself. She will come home fresh from a birthday party where the girls are getting mad at her for something and it’s just that she didn’t understand something about the rules or that it wasn’t her turn. She didn’t hear the directions for something they were doing, that kind of thing.

“She always wears a smile and seems so bubbly but she comes homes and can be very frustrated. It’s hard. She kind of shuts down because her processing is slower than ours. She spends a lot of time trying to keep up with conversations, so she’s mute for like 30 minutes because she’s trying to detect who is talking, which voice is going.”

Learning TikTok dances? Forget about it, says Hailey. “I can never do that because they teach in a group and talk fast and it’s hard to keep track of.” Ditto for Taylor Swift concerts. While most of her girlfriends are Swifties, she can’t keep up. “They know the lyrics to every single song,” says her mom. “Hailey didn’t go to a Taylor Swift concert because it’s very hard for her to catch onto songs.”

“Hailey is a model student,” says her Condit Elementary fifth-grade teacher Melanie Mulhollan. “She loved to read and write. And she loved to sit right in front of me, watching me always. She always loved it when I read novels out loud. She was so expressive and interested. “

On the flip side, says Mulhollan, “I know it was hard for her at recess. She had to be facing her friends to feel and understand the nuances of what was going on, to be able to participate in the fun.”

“It makes me feel sad that some people don’t realize about her hearing and how she’s different,” says her brother Jaden, 10.

“Yeah, but Jaden doesn’t see me as anyone different,” chimes in Hailey. “We just hang out like normal siblings.”

There are certain advantages when the cochlear implants go to their charging station at night, Hailey says. “Total silence. If it’s thundering outside, it’s not a big deal. I sleep. It’s nice.”

“Hailey likes her silent world, especially in the morning,” says Leslie.

SIBLINGS Hailey’s 10-year-old brother, Jaden, says it makes him sad when others don’t understand how Hailey’s hearing loss impacts her daily life. “Yeah, but Jaden doesn’t see me as anyone different,” says Hailey. “We just hang out like normal siblings.” (Photo: Dylan Aguilar)

But even with the cochlear implants out, words can reach Hailey in a different way, says her mom. When her parents speak “I love you” loudly into an unaided ear, Hailey feels the vibration, deep and rich with rhythm.

“To know the vibration of ‘I love you’ is really special,” says her mom. “She can feel it. That’s pretty cool.”

Editor’s note: Alex’s book, The Sound of VICTORY: A Young Boy’s Journey Through Hearing Loss and Sports is available through Amazon, Target, and Barnes & Noble.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.